Managing bias

You make thousands of rational decisions every day — or so you think…

From what you’ll eat throughout the day to whether you should make a big career move, research suggests that there are a number of cognitive stumbling blocks that affect your behavior, and they can prevent you from acting in your own best interests.

Here, Business Insider has rounded up the most common biases that confound our decision-making.

People are over-reliant on the first piece of information they hear. In a salary negotiation, whoever makes the first offer establishes a range of reasonable possibilities in each person’s mind.

People overestimate the importance of information that is available to them. A person might argue that smoking is not unhealthy because they know someone who lived to 100 and smoked three packs a day.

The probability of one adopting a belief increases based on the number of people who hold that belief. This is a powerful form of groupthink and is the reason why meetings are often unproductive.

Failing to recognize your own cognitive biases is a bias in itself. People notice cognitive and motivational biases much more in others than in themselves.

When you choose something, you tend to feel optimistic about it, even if that choice has flaws. Like how you think your dog is awesome — even if it bites people every once in a while.

This is the tendency to see patterns in random events. It is key to various gambling fallacies, like the idea that red is more or less likely to turn on a roulette table after a string of reds.

We tend to listen only to information that confirms our preconceptions — one of the many reasons it’s so hard to have an intelligent conversation about climate change.

Where people favor prior evidence over new evidence or information that has emerged. People were slow to accept that the Earth was round because they maintained their earlier understanding that the planet was flat.

The tendency to seek information when it does not affect action. More information is not always better. With less information, people can often make more timely decisions.

The decision to ignore dangerous or harmful information by burying one’s head in the sand like an ostrich. Research suggests that investors check the value of their holdings significantly less often during bad markets.

Judging a decision based on the outcome — rather than how exactly the decision was made in the moment. Just because you won a lot in Vegas doesn’t mean gambling your money was a smart decision.

Some of us are too confident about our abilities, and this causes us to take greater risks in our daily lives. Experts are more prone to this bias than laypeople, since they are more convinced they are right.

When simply believing that something will have a certain effect on you causes it to have that effect. In medicine, people given fake pills often experience the same physiological effects as people given the real thing.

When a proponent of an innovation tends to overvalue its usefulness and undervalue its limitations. Sound familiar, Silicon Valley!?

The tendency to weigh the latest information more heavily than older data. Investors often think the market will always look how it looks today and make unwise decisions.

Our tendency to focus on the most easily recognizable features of a person or concept. When you think about dying, you might worry about being mauled by a lion. as opposed to what is statistically more likely, dying in a car accident.

Allowing our expectations to influence how we perceive the world. An experiment at a football game between students from two universities showed that one team saw the opposing team commit more infractions.

Expecting a group or person to have certain qualities without having real information about the person. It allows us to identify strangers as friends or enemies quickly, but people tend to overuse and abuse it.

An error that comes from focusing only on surviving examples, causing us to misjudge a situation. For instance, we might think that being an entrepreneur is easy because we haven’t heard of all those who failed.

Sociologists have found that we love certainty — even if it’s counterproductive. Eliminating risk entirely means there is no chance of harm being caused.

So what?

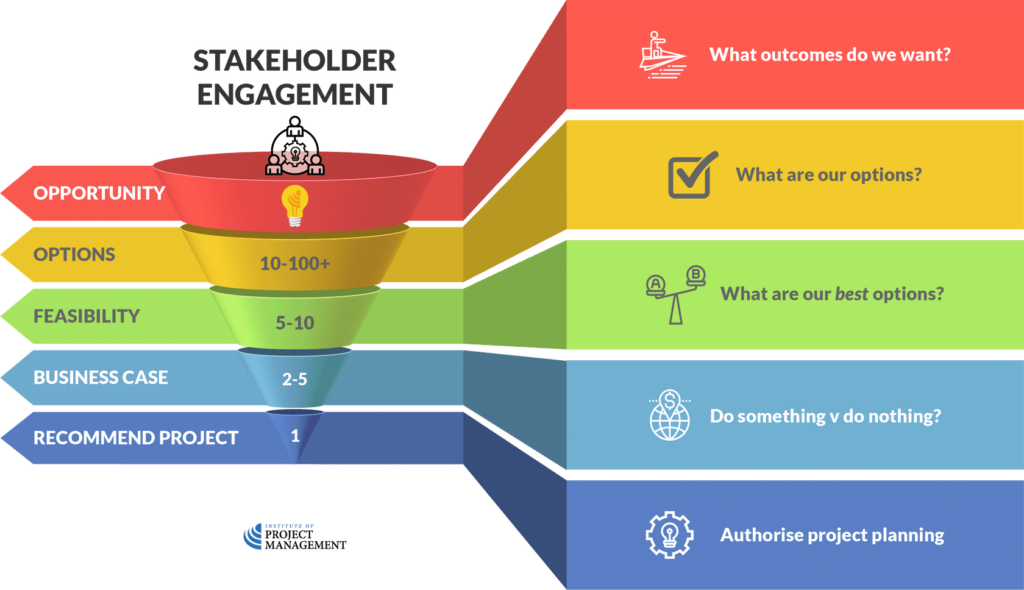

An organized and systematic decision-making process usually leads to better decisions.

As discussed, the decision-making process looks a lot like the business case development process we explored in the first Module, doesn’t it!

That’s because the business case is a framework we use to arrive at a very specific type of decision – whether or not to begin planning a project.

Ultimately, decision-making is a skill, and skills can usually be improved.

As you gain more experience making decisions, and as you become more familiar with the tools and structures needed for effective decision-making, you’ll improve your confidence in this regard.

At the end of the day, working on your decision-making will improve project delivery and outcomes and make you a better project leader.