The decision-making process

Ultimately, a project is nothing more than the sum of its decisions.

Whether you’re deciding which person to hire, which supplier to use, or which task to crash, the ability to make a good decision with the available information is vital.

It would be easy if there were one formula you could use in any situation, but there isn’t – each decision presents its challenges, and we all have different ways of approaching problems.

So, how do you avoid making bad decisions – or leaving decisions to chance?

1. Source reliable data

As a project manager, you will use tools such as spreadsheets, project programs, or web-based apps to keep track of projects currently in the pipeline, budgets, tasks, etc.

It is also most likely that on a weekly or even daily basis, you will run reports, check figures, and follow up on tasks and assignments as necessary.

This is a great way to keep tabs on project status and see overall progress.

By keeping records and notes, whether manually or digitally, it is safe to analyze this data and use it to make informed decisions.

For example, suppose a team member tells you that a particular customer wants to change the specifications of their product halfway through the delivery stage. What are some of the implications that go along with this?

How will this impact the schedule? How will this impact the budget?

These things need to be addressed before getting back to the customer with a firm proposal.

Remember earlier when we said garbage in – garbage out?

Decisions are often only as good as the data they are predicated on, so it is your responsibility as a project manager to ensure you always have accurate and up-to-date project records.

2. Establish a positive environment

If you’ve ever been in a meeting where people seem to be discussing different issues, then you’ve seen what happens when the decision-making environment hasn’t been established.

That’s why it is vital for everyone to understand the issue before making a decision.

This includes agreeing on an objective, ensuring the right issue is being discussed, and agreeing on a process to move the decision forward.

You also must address key interpersonal considerations at the very beginning: have you included all the stakeholders?

And, do the people involved in the decision agree to respect one another and engage in an open and honest discussion?

After all, if only the strongest opinions are heard, you risk not considering some of the best solutions available.

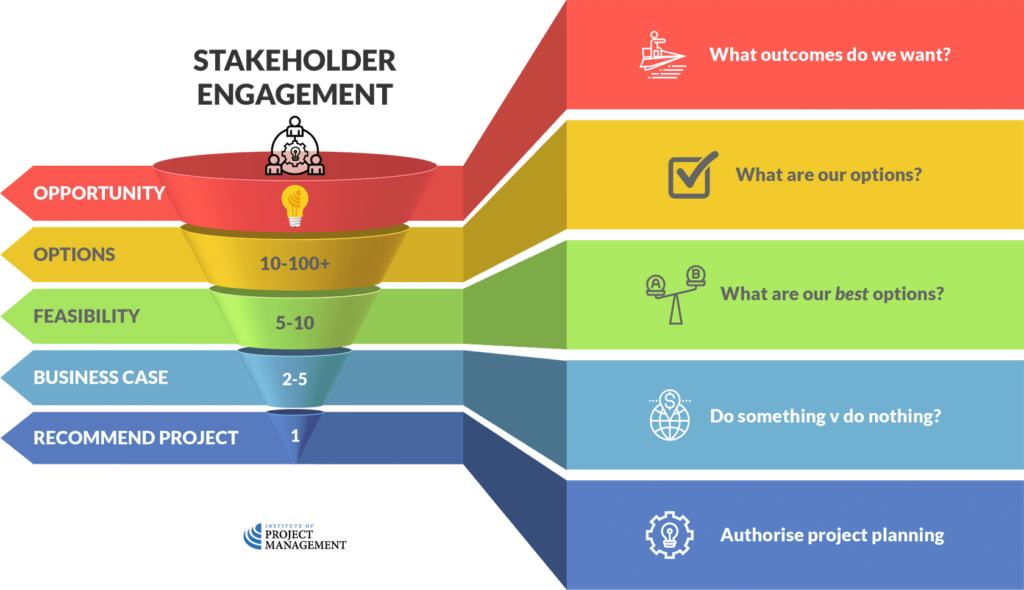

3. Generate potential solutions

Another critical part of a good decision process is generating as many good alternatives as sensibly possible to consider.

If you simply adopt the first solution you encounter, you’re probably missing many even better alternatives.

The creativity techniques we identified back in the first Module are as applicable at the start of the project as they are at the end.

Use brainstorming, mind-mapping, affinity diagramming, and the Delphi technique to get the most out of your stakeholders.

These methods do not need the complete treatment of a one-day facilitated workshop to be effective – you can do a quick and effective brainstorm in just ten minutes when all the participants understand the process and are competently led.

When you generate alternatives, you force yourself to dig deeper and look at the problem from different angles.

If you use the mindset ‘there must be other solutions out there,’ you are more likely to make the best decision possible.

If you don’t have reasonable alternatives, then there’s really not much of a decision to make!

4. Evaluate alternatives

When you are satisfied that you have a good selection of realistic alternatives, you’ll need to evaluate each choice’s feasibility, risks, and impacts.

But you already know how to do this, don’t you!

Again this is something we explored in Project Initiation that can be applied to every project decision you make.

Ask the following questions:

- What are our options?

- Are these options feasible?

- What are the costs and impacts of this decision?

- What if we do nothing?

- Does it expose us to any residual or secondary risks?

Exploring alternatives is often the most time-consuming part of the decision-making process.

It sometimes takes so long that a decision is never made!

To make this step efficient, be clear in your mind about the factors you want to include in your analysis, and be sure to communicate the criteria to contributing stakeholders.

5. Decide

Making the decision itself can be exciting and stressful.

To help you deal with these emotions as objectively as possible, use a structured approach to the decision.

This means looking at what’s most important in a good decision.

Methods such as the nominal group technique introduced earlier are an effective way of making group decisions, and the multi-criteria analysis technique is a semi-statistical aid to the process.

More often than not, though, the project manager does not have the luxury of time that these approaches demand.

Two shortcuts to decision-making are delegation and escalation.

Delegation allows subordinate team members to make the decision for you.

It assumes that the delegated decision-maker is competent to make the decision, but also depends on you trusting them to make it and supporting their judgment.

Escalation means passing the decision up to the project sponsor or steering committee.

In that event, you will still be expected to have identified alternatives and arrive at a recommendation – just don’t be disappointed when your decision-makers decide to go another way!

One of the best decisions you will make as a project leader is to let others decide for you; after all, projects can be managed to death.

It is a nuanced skill to know when to delegate, escalate, or act.

6. Communicate and implement

We have already spent a fair bit of time in this unit discussing how to communicate effectively and efficiently.

You can try to force your decision on others by demanding their acceptance, or you can gain their acceptance by explaining how and why you reached your decision.

For most decisions – particularly those that need participant buy-in before implementation – it is more effective to gather support by explaining the reasons for and necessity of your decision.

You should also have an action plan for implementing your decision.

People usually respond positively to a clear plan – one that tells them what to expect and what they need to do.

Quite often, team members care less about the implications of the decision on the project, and more about what it means for their workload.

7. Review your decision

With all the effort and hard work that goes into evaluating alternatives, deciding the best way forward, and delivering the outcomes, it is easy to forget to review both the decision and the process that led to it.

This is where you look dispassionately at the decision you’ve made to make sure that your process has been thorough, and to ensure that common errors haven’t crept into the decision-making process.

After all, I’m sure you can identify at least one example of the catastrophic consequences that overconfidence, groupthink, and other decision-making errors have wrought on the world today!

Including others

Decision-making is not an activity that occurs in isolation – especially on projects.

As we saw in the last topic, sourcing reliable data, generating and evaluating potential solutions, and communicating, implementing, and reviewing each decision are all steps in the process that should benefit from the input of others (groupthink aside, of course).

In project delivery, there are four main ways we make, communicate, and implement decisions: by direction, consultation, consensus, and delegation.

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

DIRECTION

Directive decision-making means making decisions based on your own ideas.

You can do this unassisted – in other words, solving the problem or making the decision based on the information you already have – or you can make a researched decision by obtaining any necessary information from stakeholders or other sources outside the project team, then deciding on the solution to the problem by yourself.

Directive decision-making is most effective when time is of the essence, the solution is apparent, or when you are leading unskilled or uncertain teams – more on that in a minute.

However, wholly directive managers will frustrate the team’s initiative and may slow down the project’s progress if they become a decision-making bottleneck.

By that, I mean if all decisions need to be made or approved by the PM, then work will constantly be stopping and starting to allow this to happen.

CONSULTATION

Consultative decision-making also requires the project manager to have the final say, but colleagues are somewhat empowered by their contributions that influence the ultimate decision.

In other words, you make the decision based on the ideas of the project team.

A project manager can source these contributions one-on-one, by sharing the problem individually with team members, or collectively, as we described in the topic on facilitating groups.

Engaging team members or stakeholders in this way may slow the process down a little, but remember, our project manager may not always have the technical expertise necessary to make the best calls, and (as we shall see in the following unit) depends on the robust contribution of the team to achieve the best outcomes for their project.

CONSENSUS

Consensual decision-making cedes control of decision-making to the team.

In this instance, the project manager only has one vote on the direction forward, and usually only uses it as a casting vote if the discussion is deadlocked or stalled.

Although in Western culture, we often think of consensual decision-making as slow, in many Eastern cultures, it is just as efficient as consultative decision-making.

This is because the preference for consultative or consensual decision-making is culturally embedded.

Imposing a Western, consultative style of group decision-making on an Asian project team may offend and disrupt work. In contrast, the project manager who always waits for consensus in a Western group will be seen as weak and ineffective.

DELEGATION

Finally, as mentioned in the last unit, decisions can also be delegated. Delegation means letting someone else make the decision.

As we saw in the last lesson, it usually refers to pushing the decision down to a team member, and we do this all the time in letting team members get on with their work; however, escalation is also a specific type of decision-making delegation when we push the decision up to senior or executive management.

There are two types of delegation: informed delegation and ballistic delegation.

Informed delegation means providing the delegate with any relevant information you possess, establishing parameters and objectives, and asking to be kept in touch with the process.

The delegate, though, is responsible for solving the problem or performing the task.

Ballistic delegation means – as the name suggests – fire and forget.

As the project manager, I will give you the information and resources you need; you come back to me when the decision is made or the task is complete.

The ability to delegate is a vital skill for any project manager, which we will explore in more detail later in this Unit.

As indicated in the last lesson, it is critically important you agree on the decision-making process with stakeholders to ensure everyone is on board with the process.