The project dream team

In as much as there are differences between projects and operations, there are distinct differences between the role of a project manager and those managing business-as-usual.

EXPERTISE

Operational managers usually have extensive technical knowledge in a specific area. They are the ‘expert-of-experts’ in that they function as the direct, technical supervisor of their teams and their work.

For example, an accountant will lead a team of bookkeepers, and a hotel manager will have worked their way up through a hotel’s various entry and supervisory roles.

Project managers may have some technical knowledge in one or two areas, but not necessarily knowledge beyond that.

Instead, they coordinate a team of specialists to work with other specialists in different technical areas.

In the same way, an orchestra conductor is not necessarily expert in playing all the instruments.

RESPONSIBILITY

Typically, operational managers have line control over their staff.

Reporting lines are clear, and hierarchies are well established.

Project managers share control over their teams with the technical experts in the project and functional (line) managers in the organization.

These differences significantly affect how you acquire and lead your project teams.

The ideal project team is a diverse mix of technical experts who can optimally deliver the tasks allocated to them.

They should also have at least basic project management skills that enable them to deliver tasks on time, to budget and scope, and to understand how their work fits into the overall project (for example, any dependencies related to it).

It is a given, however, that the worst thing you can do to a project team member is kick them off the project, whereas their day-to-day managers can get them fired from their job!

Loyalties, therefore, default to those line managers, sometimes at the project’s expense.

Indeed, for some, getting kicked off a project is a good outcome, because it means they can return to their more pressing, day-to-day work!

It is, therefore, important that project managers continually maintain positive relationships with other organizational managers to ensure:

- They get the best people for their projects (and not the ones no one else wants!)

- An appropriate and realistic balance is achieved between project and business-as-usual tasks

- Flexibility is possible when that balance is (inevitably) disturbed, and

- Team members return to operations at the end of projects with new, applicable knowledge and skills.

Organizing teams

When preparing the WBS and schedule, we make assumptions and estimates about the human resources (or people) required to deliver the project.

From a management point of view, however, it is often quite difficult to conceptualize the entire human resource allocation from a series of discrete WBS entries.

For example, the risk register lists risk owners, the stakeholder register nominates team members responsible for communication activities, and the WBS tasks designate those responsible for carrying out quality assurance and control tasks.

For that reason, on larger projects, we often prepare a separate human resource plan.

Regardless of format, the objective of a human resource plan is to ensure that each task has an unambiguous (and available) owner and that all team members have a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities.

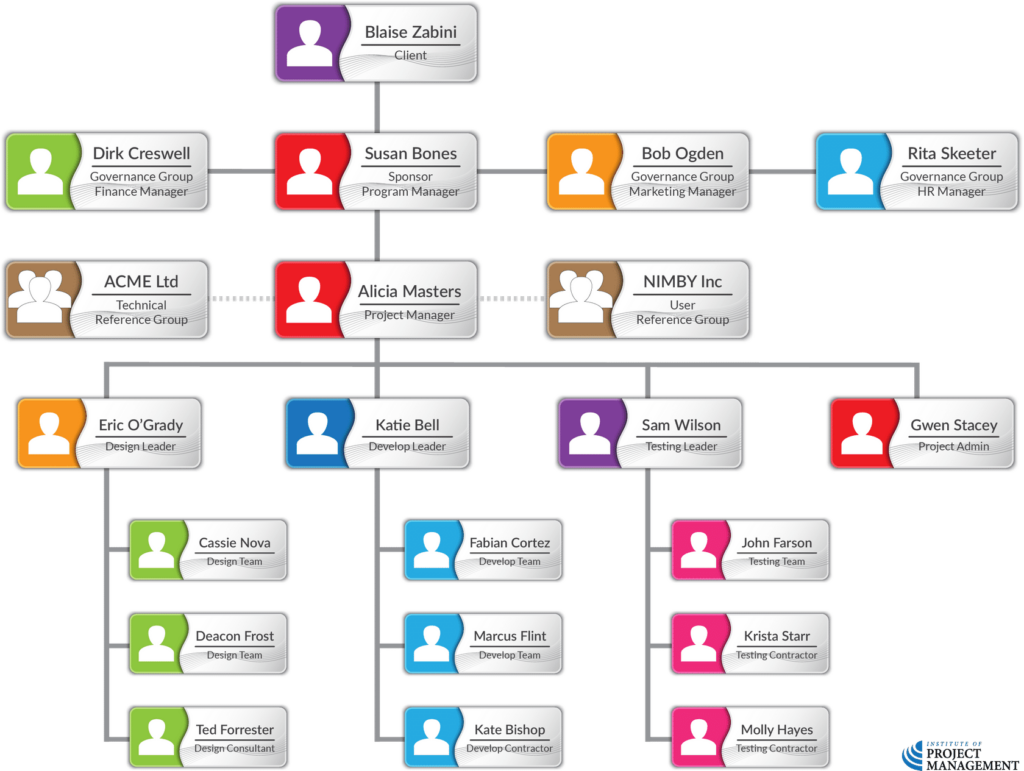

The traditional, hierarchical organizational chart structure can show positions and relationships in a graphic, top-down format.

It can be formal or informal, highly detailed or broadly framed, depending on the project’s needs.

And as indicated in the previous Module, the WBS may also be structured by team or individual levels of responsibility.

A RACI (responsible, accountable, consult, and inform) chart is another way of graphically expressing this information.

This chart maps the work to be done against the level of engagement required from each team member or stakeholder.

That said, preparing position descriptions for key project team members may still be valuable on even smaller projects.

This is especially necessary on projects where team members are responsible for multiple tasks, are new to the project environment, or have complex reporting relationships.

So, what goes into a position description?

Role

The role is a high-level or summary description of the work expected of the project team member.

Examples of project roles are scheduler, client manager, axe-grinder, and assistant econometrician – pretty much any job you can imagine!

Role clarity around the place and hours of work, as well as remuneration, should also be explicit.

Responsibilities

Responsibilities refer to the work that a project team member is expected to perform on behalf of the project.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) or other success measures may also be stipulated here.

More often than not, this will summarise and index the relevant WBS tasks.

Competencies

Competencies are the skills required to complete project tasks.

If project team members do not possess the required competencies, performance can be jeopardized.

When such mismatches are identified, responses can include training, subcontracting, or changes to the schedule or scope.

Delegated authority

Delegated authority is the right to apply project resources, make decisions, and sign approvals.

Examples of decisions that need clear authority include selecting a method for completing a task, quality acceptance, and how to respond to project variances.

Team members operate best when their levels of authority match their individual responsibilities and competencies.

Accountabilities

Finally, accountabilities list who the project team member is directly answerable to in the project – in other words, their boss.

Where a project team member has multiple accountabilities – for example, they are contributing to a variety of tasks that they do not individually ‘own’ – guidance should be provided as to their priority.

This can be done through an organizational chart or RACI matrix, as described above.

The human resources plan

There are several other project requirements that may be documented in the human resource management plan…

Staff acquisition

A number of questions arise when planning the acquisition of project team members.

For example: will the human resources come from within the organisation or from external, contracted sources?

Will team members need to work in a central location or can they work from distant locations?

What are the costs associated with each level of expertise needed for the project?

How much assistance can the organisation’s human resource department and functional managers provide to the project management team?

Resource calendars

The staffing management plan describes necessary time frames for project team members, either individually or collectively, as well as when acquisition activities such as recruiting should start.

One tool for charting human resources is a resource histogram.

This bar chart illustrates the number of hours a person, department, or entire project team will be needed each week or month throughout the project.

The chart can include a horizontal line representing the maximum number of hours available from a particular resource.

Bars that extend beyond the maximum available hours identify the need for a resource leveling strategy, such as adding more resources or modifying the schedule.

Training needs

If the team members to be assigned are not expected to have the required competencies, a training plan can be developed as part of the project.

The plan can also include ways to help team members obtain certifications supporting their contributions to the project.

Recognition and rewards

Clear reward criteria and a planned system for their use help promote and reinforce desired behaviors.

Recognition and rewards should be based on activities and performance under a person’s control to be effective.

For example, a team member to be rewarded for meeting cost objectives should have appropriate control over decisions that affect expenses.

Creating a plan with established times for the distribution of rewards ensures that recognition takes place and is not forgotten.

Safety and compliance

Policies and procedures that protect team members from safety hazards can be included in the staffing management plan and the risk register.

Relevant strategies for complying with applicable government regulations, union contracts, and other established human resource policies might also be documented here.

Staff release plan

Determining the method and timing of releasing team members benefits both the project and team members.

When team members are released from a project, the costs associated with those resources are no longer charged to the project, thus reducing costs.

More importantly, though, morale improves when smooth transitions to upcoming projects are planned.

A staff release plan also helps mitigate human resource risks that may occur during or at the end of a project – we will discuss these in more detail in the next Module.

Attention should also be given to the availability of (or competition for) scarce or limited human resources.

The business-as-usual activities of the organization and even other projects may be competing for people with the same competencies or skill sets.

Because of this, project costs, schedules, risks, quality, and other areas may all be significantly affected.