Interview purpose

After being reviewed, a well-documented project will give you a tremendous amount of insight into what worked well and where the opportunities for improving the delivery of future projects might lie.

Yet very few projects are that well documented, especially those that demand a detailed forensic review.

This is because the project documents we described in the last topic – even if complete – will only ever tell you the official story of the project; the real story of every project is usually much more gritty and complex than the paper trail will ever admit to.

This is why an essential skill for every project manager is the ability to interview key stakeholders.

The principles for interviewing stakeholders are akin to those for facilitating groups, and these are topics we have covered elsewhere in this course.

Interviews, though, are much more personal, and unlike in meetings or workshops, your objective is not to solve a problem in the moment but to purely gather data for later reflection and analysis alongside other sources of information (such as the project documents).

Critically, the stakeholders you interview will only be available for a short, set amount of time – usually an hour or so – so you must ensure that you make the absolute most of this brief opportunity.

For that reason, you should always thoroughly study the project documentation before beginning the interview, and prepare your questions on both the issues that you identify and the purpose of your review.

Conducting an interview

In the interview itself, you must allow your preconceptions to be challenged.

Do not assume that just because something was documented a certain way, this is a true and accurate record of what actually occurred.

You might (in fact, probably will) get different versions of events from your interview subjects, and dialing in the ‘truth’ can be a difficult exercise.

This is especially true of projects that have failed.

Your interview subjects may be looking to assign blame to others, talk up their own achievements, or even be openly hostile to the interview process.

I can tell you from experience that this is never pleasant for either person in the room!

Your first objective, then, should always be to make the subject comfortable.

To that end, there is rarely any reason why you should not send them the questions before the interview – you should not have the attitude of a prosecutor here, trying to get great big ‘gotcha’ moments.

Open with a bit of small talk, and what we sometimes call ‘Dorothy Dixers’.

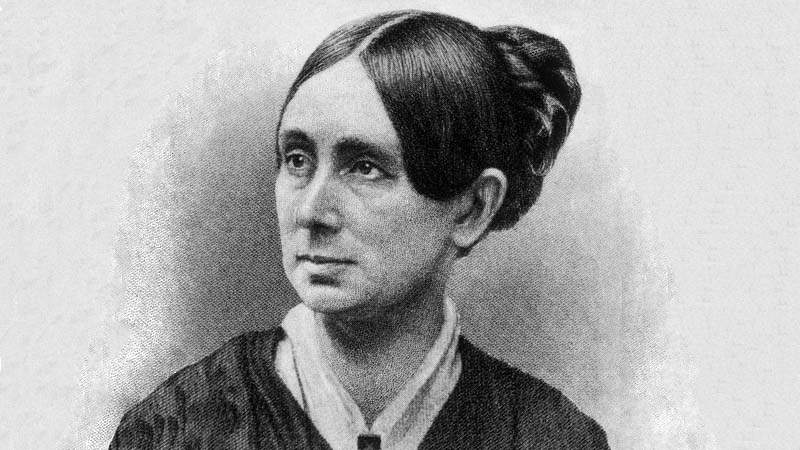

In the first half of the twentieth century, Dorothy Dix was America’s highest-paid and most widely-read female journalist.

Her advice on marriage was syndicated in newspapers around the world, with an estimated audience of 60 million readers.

Unfortunately, though, her reputed practice of writing her own questions to allow her to publish pre-prepared answers gave rise to the Australian term ‘Dorothy Dixer’.

This refers to a question from a member of Parliament to a Minister that enables the Minister to make an announcement in the form of a reply.

In other words, ask a few really soft questions everybody knows the answer to, before getting into the more technical or controversial examination.

Tips and tricks

Other tips include:

- Ask open-ended questions

- Practice your active listening

- Use silence

- Respect ‘off-the-record’ confidences (although you should always try and independently verify them)

- Explore side issues when they are relevant, but keep to the agenda

- Let the interviewee ask questions of you, and

- Reboot the interview, if necessary.

By rebooting the interview, I mean let it seemingly wrap up, and then when the subject is nice and relaxed (and probably relieved), ask that one more penetrating question they were trying to avoid.

Fans of the old American TV series Columbo will know what I mean!

For the most part, though, interviewees will want to be helpful – it is your job to show them how they can.

After all, a really good series of interviews will ultimately form the backbone of your forensic project review.