Root cause analysis turns project issues into insights, then into SMART actions so future teams can prevent, reduce, or better manage the same risks.

For want of a nail the shoe was lost…

For want of a shoe the horse was lost…

For want of a horse the knight was lost…

For want of a knight the battle was lost…

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost…

…so a kingdom was lost—all for want of a nail.

English proverb believed to be based on the legend of King Richard III and the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485)

Key terms

Root cause analysis: A method used to look beyond symptoms and identify the deeper factors that made an issue possible.

5 Whys: A questioning technique where you keep asking “Why?” to uncover contributing causes beneath the surface issue.

Mind mapping: A visual way of exploring multiple possible causes around a central issue without forcing a linear order.

Fishbone diagram: A structured diagram where causes are grouped into categories like people, process, or tools to make patterns easier to see.

Correlation: When two things happen at the same time but one does not necessarily cause the other.

Causation: When one event directly contributes to or triggers another event.

Recommendation: A proposed action that turns a lesson into something that can be done differently in the future.

Start–Stop–Continue: A simple way to group recommendations into what should begin, stop happening, or be repeated in future projects.

SMART recommendation: A recommendation written so it is Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-bound.

12.6.1: Root cause analysis

Capturing lessons as they happen is powerful — but to make them useful, we need to understand why they happened.

That’s where root cause analysis comes in.

The goal isn’t to hunt for a final “ultimate cause,” because projects are rarely that simple. Instead, the goal is to identify the most significant causes that we can influence — and decide what can be done next time to avoid, reduce, or shift the impact.

Six Sigma and the “5 Whys”

A common tool used in Six Sigma (a quality management methodology) is the 5 Whys technique.

In this approach, you take an issue and ask “Why?” repeatedly (or five times) to uncover deeper contributing factors.

- Why did the report contain errors?

- Because the data was rushed.

- Why was it rushed?

- Because the deadline wasn’t clear.

- Why wasn’t it clear?

- Because the scope change was approved verbally, not documented.

This approach is good because it challenges surface assumptions and forces people to look beyond the obvious explanation.

It’s also easy to apply in real time, even in a few minutes at the end of a meeting or task.

However, it can also be limiting, because real project environments are not linear — multiple causes often interact, and asking “why” in a straight line can give a false sense of simplicity.

It can also push people toward finding a single “final cause,” which doesn’t reflect how systems actually behave.

Alternate approaches

Mind-mapping, which we introduced in the Unit on Risk Management, is a simple visual tool that helps teams explore causes without forcing them into a straight line of reasoning.

You start by writing the issue in the center of a page, then branch out freely with every possible contributing factor—people, timing, tools, governance, communication, assumptions, and more.

Because it doesn’t impose hierarchy, mind mapping encourages open thinking and surfaces unexpected connections that a linear method like the 5 Whys might miss.

Its strength is in helping people “see” complexity before narrowing down to the points of intervention.

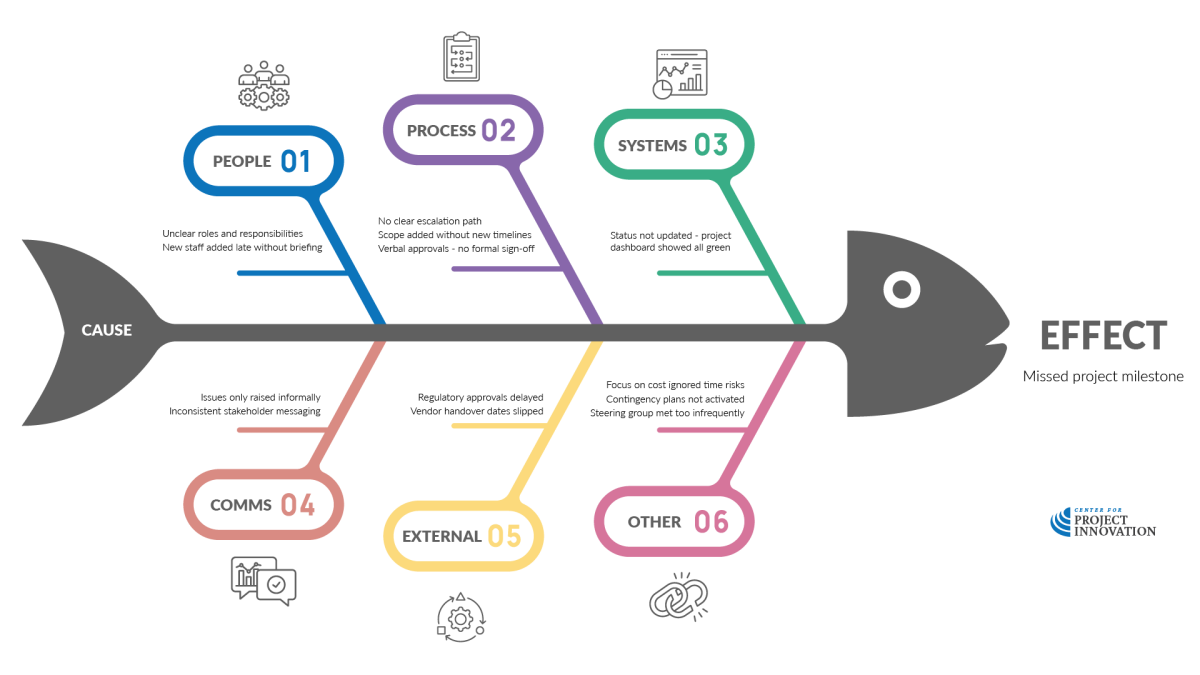

A fishbone diagram (also called an Ishikawa diagram) is a more structured version of root cause mapping.

Unlike a mind map, which branches freely in all directions, a fishbone diagram organizes contributing factors into predefined categories such as people, process, tools, communication, or governance.

Each “bone” represents one of these categories, and causes are listed along the spine leading to the main issue.

This structure helps keep discussions focused and avoids drifting off-topic, making it useful in formal review settings.

Where mind mapping encourages expansive thinking, a fishbone diagram helps narrow and organize that thinking into something that can be acted on.

When identifying root causes, it’s critical to distinguish what actually caused an issue versus what simply happened at the same time.

For instance, a team might observe that “Every time a stakeholder workshop was held, project delays increased.” That’s a correlation.

It doesn’t mean the workshop caused the delay—more likely, workshops were called because the project was already in trouble.

If we confuse correlation with causation, we risk fixing the wrong thing, removing practices that were actually helping, or designing controls for symptoms instead of real drivers.

Ultimately, the purpose of root cause analysis is not to assign blame or find a single perfect answer, but to understand the deeper factors that made an issue possible so that future projects can intervene earlier and more effectively.

By looking beyond the surface symptoms, it helps identify where small changes in process, communication, governance or decision-making could have changed the outcome.

Done well, it turns one project’s pain points into practical guidance that improves the way future teams work.

12.6.2: Making recommendations

Once root causes have been explored, each one should be treated as a potential future risk, not just an explanation of what went wrong this time.

A cause only becomes useful when it informs a change in behavior, process, or decision-making.

That’s where recommendations come in.

Recommendations translate learning into action. They answer a simple forward-looking question: “If this cause appears again in a future project, what could we do differently to reduce its impact or prevent it altogether?”

To be taken seriously by the organization, recommendations should be:

- Logical – clearly linked to a lesson identified in the review

- Practical – achievable without requiring a complete organizational overhaul (unless an urgent systemic risk is identified)

- Prioritized – either numbered or grouped by importance or theme

- Accessible – written in clear language, with each recommendation able to stand alone and still make sense

Importantly, not every lesson requires action. Some insights exist simply to inform awareness.

Start-stop-continue

A straightforward way to present recommendations from a project review is through the start–stop–continue framework.

START

Identify actions, processes, or habits that were missing but would add value in future projects. These often come from causes where a preventive step could have reduced risk or improved flow.

STOP

Highlight practices that created unnecessary work, confusion, or risk. These are drawn from causes where an existing behavior contributed to delays, rework, or tension.

CONTINUE

Capture practices that clearly contributed to success and should be retained or even formalized. These prevent successful behaviors from being lost simply because they weren’t recorded.

The start-stop-continue model helps keep recommendations balanced, constructive, and usable. Without a “Continue” category, reviews tend to focus only on faults, which can create defensiveness and reduce engagement.

After all, negative outcomes have 7–10 times the emotional impact of positive ones. By deliberately including strengths, project narratives avoid skewing toward failure and reinforcing a cycle of defensiveness.

It also makes recommendations easier to prioritize and implement, as each category clearly signals a different type of action: introduce, eliminate, or reinforce.

SMART recommendations

To ensure recommendations don’t just die in your review but are actually implemented, they need to be written in a task-ready format.

One widely adopted method for doing this is the SMART framework, which we introduced in Unit 3.

It was designed as a practical way to turn vague improvement goals into clear actions that managers could assign, track, and deliver. SMART defines actions as:

- Specific – Clear enough that someone knows exactly what is being proposed without needing extra interpretation.

- Measurable – There is a visible indicator of progress or completion.

- Assignable – Explicitly identifies who is responsible for carrying out the action, so it doesn’t sit as a vague suggestion with no owner.

- Realistic – Realistic within the organization’s resources, authority, and constraints.

- Time-bound – Includes an expected timeframe or trigger for when it should be actioned or reviewed.

Writing recommendations this way allows them to function as standalone tasks or even full improvement projects, rather than vague suggestions that get acknowledged but never implemented.

For example, “Improve stakeholder communication” is too broad.

A SMART version might read: “Within the next three months, introduce a one-page stakeholder summary template to be included in all status reports to ensure consistent messaging across project teams.”

By framing recommendations in SMART terms, you make it possible for the organization to assign ownership, allocate resources, track progress, and report back.

This is how lessons actually become part of organizational practice, rather than remaining as a curious insight that never leaves the page.

12.6.3: Every project ever?

Some projects simply don’t warrant a deep lessons-learned investment.

If the project is a true one-off, will never be repeated, or sits well outside your normal operating model (for example, a unique event or a bespoke, third-party turnkey solution with no follow-on), the transferable value may be low.

In those cases, capture essentials for the record, note any contractual or governance takeaways, and move on.

By contrast, innovative, disruptive, or failed projects usually yield the richest learning.

When you test new delivery models, technologies, suppliers, funding arrangements, or stakeholder engagement approaches, you expose the organization’s real operating seams: where governance held or wobbled, how change was absorbed, what accelerated progress, and what quietly created drag.

Failed or troubled projects, in particular, surface repeatable failure modes (slow escalation, ambiguous ownership, optimistic reporting, poor benefits anchoring) that, once named and addressed, can lift performance across the whole portfolio.

You can also pre-select which projects merit deeper review using a simple screen:

- Strategic risk: Does the project touch core strategy, regulatory exposure, or executive promises?

- Spend and scale: Is the financial impact large enough that small improvements generate big savings?

- Community or customer impact: Will outcomes affect reputation, safety, service levels, or equity?

- Governance sensitivity: Were there escalations, political pressure, or media interest?

- Replicability: Is this a pattern you will run again (programs, rollouts, platform upgrades)?

- Novelty: Did we try a new method, contract type, vendor ecosystem, or tech stack?

As a rule of thumb, the more repeatable, visible, and strategically consequential the pattern, the deeper the review.

Focus your heaviest learning effort where it will pay dividends on the next wave of similar work, and keep lighter-touch reviews for true outliers.

12.6.4: The reviewer

As a final note, who leads the review process can also have a direct influence on the type of insights captured, the level of candor, and how seriously the findings are adopted.

Who leads the review should match the level of risk, politics, and learning value of the project.

The project manager who delivered the work brings deep insight into real decision dynamics and undocumented workarounds, but because they are so close to the delivery, their perspective is best used as a contributor of raw insight, not as the lead reviewer of formal lessons.

A project manager from elsewhere within the organization strikes a strong balance for most reviews — they understand internal context and governance culture, so their findings are more likely to be adopted, yet they have enough distance to challenge decisions without it becoming personal.

However, when the project is high-risk, politically exposed, or has failed in a public or sensitive way, a fully independent reviewer can create the necessary frank and fearless critique that internal teams may struggle to produce.

| Reviewer Type | Strengths | Risks / Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| The project manager | Knows every decision and nuance of delivery; can highlight subtle judgment calls and informal workarounds that never made it into records. | May unconsciously justify decisions rather than critique them; can be defensive if review feels personal; insight may be filtered by pride or fatigue. |

| A PM from elsewhere in the organization | Brings internal context and understands governance culture, politics, and delivery constraints; more likely to produce lessons that the organization will actually adopt, as they speak the same language. | Risk of internal bias or mutual protection (“we all know how things work here”); may accept systemic dysfunction as normal rather than challenge it. |

| Independent external reviewer | High objectivity; able to challenge sacred assumptions and political narratives; more likely to surface uncomfortable truths; no internal alliances to protect. | Higher cost; may miss cultural or operational context; lessons may be intellectually correct but harder to implement if framed without sensitivity to internal realities. |

A useful way to think of it is that the project PM feeds the real story, an internal PM translates it into organizational learning, and an independent reviewer is brought in when truth needs distance from internal politics or when credibility with external oversight is essential.