Learn how to wrap up projects the right way—verify work, gain sign-off, hand over smoothly, and close with confidence while keeping clients happy.

Begin with the end in mind.

Dr. Stephen R. Covey, Management Consultant

Key terms

Verification: The process of checking that all work has been completed properly and meets agreed standards before handover.

Acceptance criteria: A client-defined list of conditions that a deliverable must meet to be considered complete and ready for sign-off.

Internal sign-off: Approval from the sponsor or steering committee confirming the project team has met internal delivery obligations.

Client acceptance: The moment when the client formally agrees that the deliverables meet expectations and takes responsibility for them.

Operational ownership: The state where users or operational teams can manage the deliverables without relying on the project team.

Handover: The structured transition of deliverables, access, and responsibility from the project team to the client or operations team.

Defects liability period: A defined timeframe where the delivery team remains responsible for fixing issues after handover.

12.2.1: Checking it twice

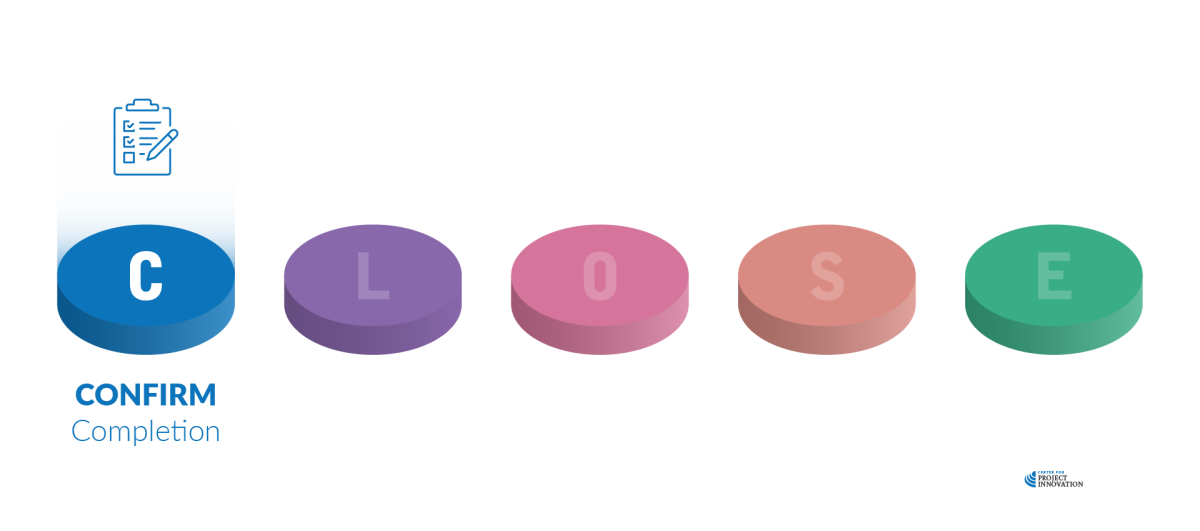

Let’s now take a deeper dive into the first four of those five steps to project close.

Knowing when a project is truly complete isn’t as simple as reaching the end of a task list. Just because something ‘feels’ complete from the project team’s perspective doesn’t mean it meets stakeholders’ expectations.

Of course, you should trust your team, but you should also verify their work before handing it over to the client.

The work breakdown structure (WBS) breaks the scope into clear, actionable components. It should be used as the foundation for verification. Every task, no matter how small, needs to be reviewed.

This foremost involves clearing all deferred or pending items. The “we’ll do it later” tasks have a habit of being forgotten.

So if a task still exists in a project tracking tool, backlog, or notebook, it hasn’t truly been completed. And if there’s no record of acceptance, it hasn’t been delivered.

This is where many projects fall short—they reach what feels like the finish line but leave loose ends that later create rework, support issues, or client dissatisfaction.

Like stakeholder engagement, testing and validation always take longer than expected. However much time you think you need—double it, and it still won’t feel like enough.

Good verification asks, “Can this break, and if so, how?”

Trying to break it on purpose is better than waiting for a client or end user to do it for you.

In infrastructure and engineering projects, this may involve formal testing schedules, engineering reports, compliance checks, or regulatory inspections (for example, asbestos clearance, load testing, safety certifications).

In digital or software projects, this might mean staged releases, user acceptance testing, or performance validation.

Importantly, verification is not a one-time event. It should run as an ongoing process across major phases, not as a rushed activity squeezed in at the end.

Once everything has been verified against the WBS, tested against expected use, and confirmed to meet client, compliance and regulatory requirements, you can move to internal sign off.

This involves presenting the completed deliverables to the sponsor or steering committee and seeking written approval to hand them over to the client or operational owner.

At this point, you should be confident that:

- Nothing has been left unfinished.

- All deferred items are either completed or formally agreed for future phased work.

- You are not relying on assumptions—only confirmed acceptance.

Only then can you confidently say: “This project is ready to close.”

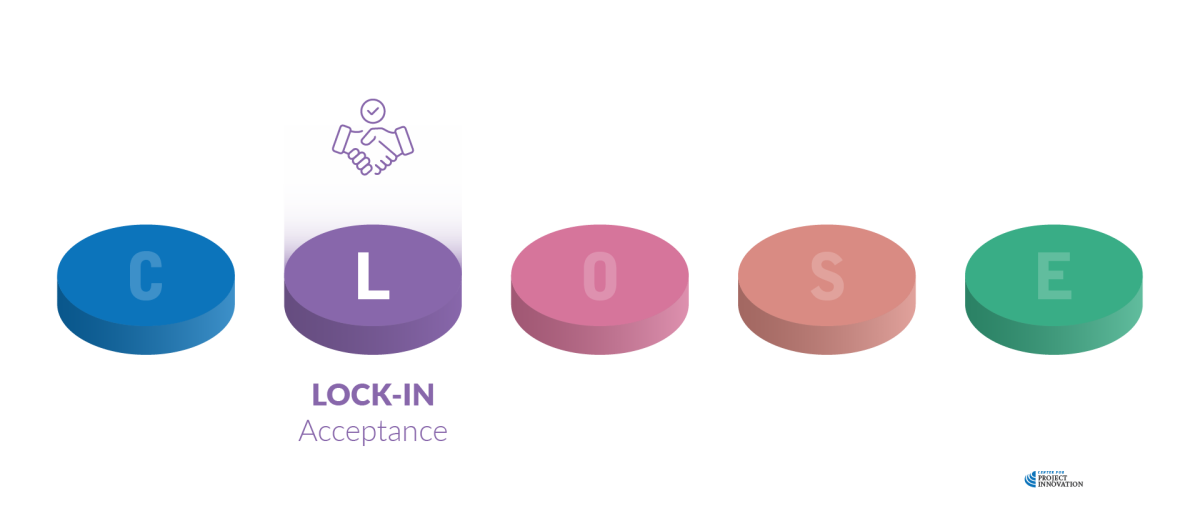

12.2.2: Acceptance criteria (remember these?)

Every task in a good WBS has its own acceptance criteria, but these criteria are written with a specific purpose: to ensure that each task is ready to be delivered to the next step in the delivery plan.

In other words, they are internally derived, usually without reference to the client.

For that reason, it is a mistake to assume a project is complete just because all WBS tasks have been performed.

Even in the absence of acceptance criteria, a project is not completed until the client accepts the deliverables and takes responsibility for the outputs of the project.

In a formal contract with a customer outside the organization, specific acceptance criteria will be included in the contract terms.

However, even these criteria are rarely a full statement of the client’s expectations.

A crucial mistake made by inexperienced project managers is not requesting, up front, a written agreement of acceptance criteria.

After all, if these criteria do not exist, the client can forever claim that the deliverable is not exactly what was requested, and the project continues.

Likewise, projects internal to an organization—especially those that involve different organizational groups—will suffer the same consequences if there is not a memorandum of agreement among the groups that specifically details the acceptance criteria.

But you already know this!

Back in Unit 5 we warned that this was coming, and hopefully you kept your criteria (ideally formatted as a checklist) up-to-date as changes to the project plan were proposed and approved.

Regardless of whether project-level customer acceptance criteria are in place, when handing over, walk the client through the deliverable(s) and explain why you think the project is fit-for-purpose.

At this time, you should also clarify any uncertainty and disclose any risks.

Only then can formal sign-off and delivery be achieved.

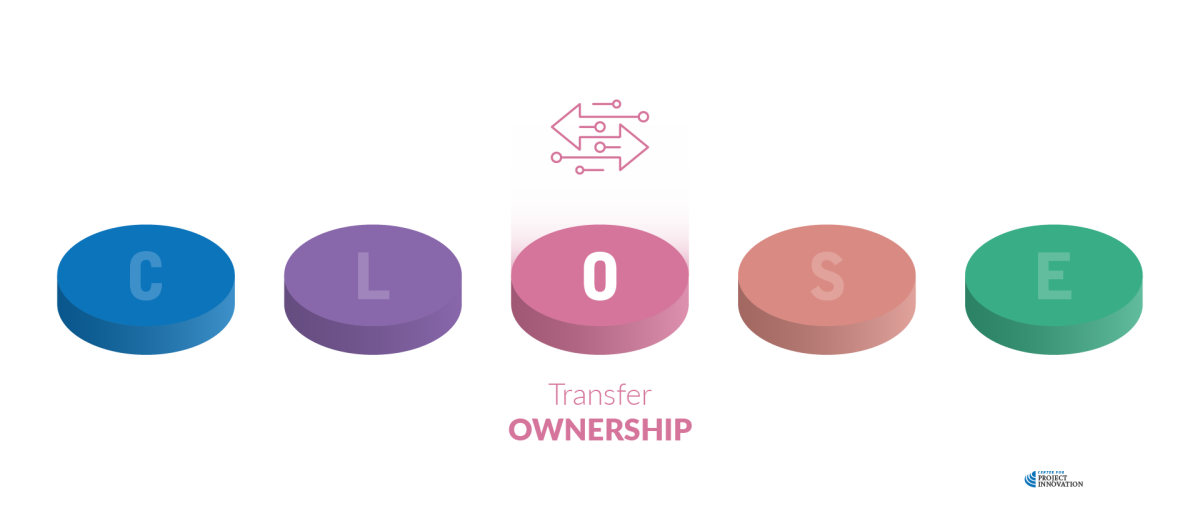

12.2.3: Are we there yet?

In many projects, the moment the client signs off on the deliverables is treated as the finish line. But formal acceptance is not the same as operational ownership.

A project is only truly off your books when the people who will use or manage the output can operate it confidently without relying on the project team.

That means ownership transfer needs to be planned, budgeted, and supported, not left as an afterthought.

Importantly, the transition into live use comes with costs—training time, documentation, support channels, onboarding resources—and these must be budgeted for and protected, especially when costs overrun in other areas of delivery.

Unfortunately, many projects run out of funding right when users actually need the most support!

User guidance must also be practical, accessible, and easy to reference later. Examples include:

- Static guides: PDF manuals, printed quick guides, checklists.

- Interactive resources: knowledge bases, wiki-style help, embedded support links.

- User training: live and repeatable resources—recorded sessions, walkthrough videos, or guided tutorials—that users can return to when they need a refresher.

All guidance must cover troubleshooting and real use cases, not just ideal scenarios.

The goal isn’t just to provide documentation—it’s to ensure users can solve problems without calling the project team back in.

Ownership transfer may also look different depending on the context.

In construction and infrastructure projects, a defects liability period (often 12–24 months) means the contractor must return to fix issues after practical completion, or suffer a financial penalty.

In other projects, money-back guarantees or warranties may be included.

Quite often, though, a completely different business unit or service team takes responsibility for this.

Therefore, as part of the transfer, you must ensure everyone knows who to contact (both internally and externally), and there is clarity on what the project team will and will not support.

Ownership should be visible, not just assumed; otherwise, the project manager’s phone will keep ringing long after you’ve moved onto your next three projects.

A clean handover is not just good project management—it’s good business. It protects the client relationship, prevents scope creep after completion, and allows the project team to exit professionally without leaving confusion behind.

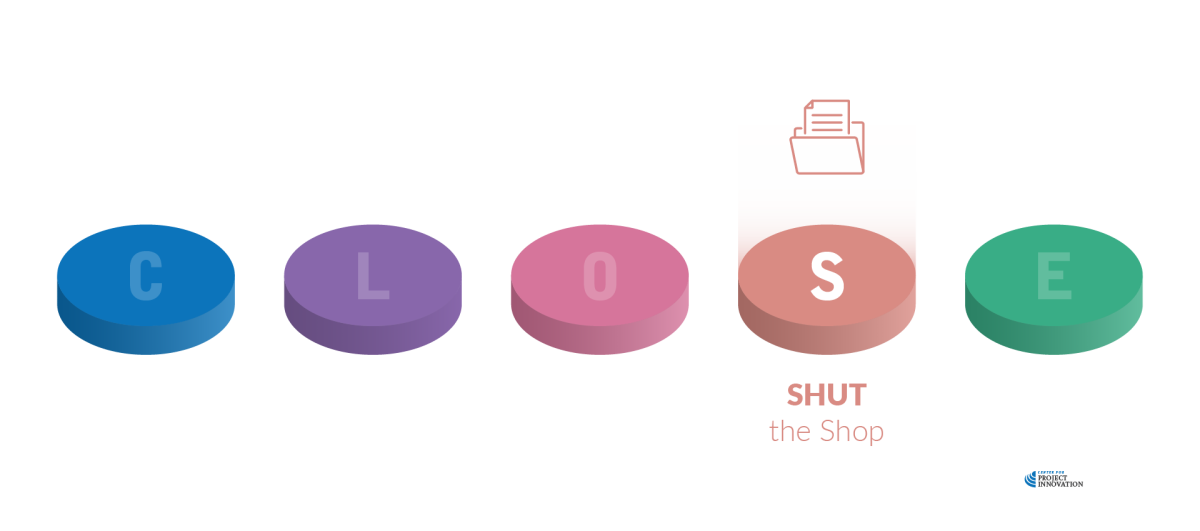

12.2.4: Loose ends

Project closure is often imagined as a final phase—a neat block of time where everything is wrapped, filed, and handed over.

In reality, closure is a rolling activity, not a single event. Parts of your project are constantly completing: work packages end, milestones are met, people finish their contribution and move on, equipment is no longer needed.

If you wait until the very end to begin administrative close, you will be overwhelmed.

This is where professional project managers distinguish themselves from those simply trying to survive delivery. The mindset shift is simple: start closing early.

At each stage of delivery, ask: “Is there anything here I can close, hand over, offboard, archive, or release now rather than later?”

By progressively clearing documentation, returning unused resources, capturing knowledge when people roll off, and closing out minor contracts or access permissions early, you prevent a mountain of administrative pressure from piling up at the end, right when funding, attention, and goodwill are at their lowest.

Hopefully, your final steps in shutting down a project described below have benefited from this mindset and process.

Document archive

All the project documentation must be formally reviewed for outstanding action, cataloged, and archived. Also, check that all relevant information has been communicated to stakeholders.

As well as all the initiation, planning, and delivery documents described elsewhere in this course, documents for review (in all their configurations) might include:

- Contracts

- Meeting minutes

- Status reports

- Issue and change logs, and

- General correspondence

Resource reassignment

Often, a project involves buying or renting equipment and facilities, or using assets supplied by the client. All physical equipment must be accounted for, returned, or transferred, and any organizational assets used may need to be reconditioned, reassigned, or depreciated for financial purposes.

In addition to physical resources, all access and privileges granted during the project must be formally reviewed and closed out. This includes building keys, swipe cards, temporary logins, system admin rights, shared passwords, guest accounts, and VPN or remote access.

Keeping access after handover creates security risks and blurred accountability.

Just as importantly, new owners should be granted full control over systems, which means ensuring that all other users—including the project team—are removed or locked out once responsibility has transferred.

This step protects both sides: the client gains clear ownership and control, and the project team is no longer exposed to post-handover liability.

Don’t forget the people!

As delivery winds down, it’s easy to focus on contracts, documents, and technical closure and overlook the most valuable resource a project ever had — the people who delivered it.

Team members often begin to roll off before formal closure, and once someone has officially moved on, you lose access not just to their time, but to their insight, records, and informal knowledge.

Once they’re gone — especially in digital environments where personal drives and project notes are scattered — they’re gone.

Where possible, a project manager should plan people offboarding just as deliberately as equipment and access offboarding. This means:

- Confirming that all reports, working files, personal drive notes, checklists, test logs and informal records have been transferred or archived centrally.

- Ensuring that any local storage (laptops, personal folders, shared drives, collaboration tools) has been reviewed so that critical knowledge isn’t trapped in files that disappear when accounts are closed.

On the career side, people who worked on the project should not simply vanish back into the organization. The project manager plays a role in signalling their contribution — through performance feedback, recommendation notes, or career development input.

Without this, many staff members return to business-as-usual roles where their newly developed skills go unseen or underutilized, leading to stalled development or even disengagement.

Finalize client relationships

Actually, ‘finalizing’ is the wrong word here – one of the key organizational objectives of any project should be to make clients so happy they want to come back with other projects!

At the very least, it is the time to extend a relationship that allows periodic discussions about how the deliverables are serving the customer’s needs (outcomes measurement) and whether there might be additional work for the provider organization in the near future.

12.2.5: Celebrate success

Finally, it is a mistake not to celebrate success, even if those successes were limited or hard-earned in a difficult project.

Many organizations skip this step because by the end of a project, team members are already being reassigned, contractors have long gone, and contributors start disappearing as soon as their tasks are complete.

An official closing moment, whether it’s a grand opening gala or a simple morning tea, needs to be treated like any other project activity: scheduled, costed, and owned by someone.

It doesn’t need to be spectacular, but it does need to be intentional.

Celebrating a project’s close serves four key purposes:

- It marks the official end of the project for the team, giving people a collective and definitive closure rather than just having them drift away.

- It acknowledges effort, not just outputs, recognizing the work done by individuals and teams (and no small measure of shared trauma).

- It opens the door to meaningful reflection and lessons learned, as people are more willing to contribute insights when they feel their involvement has been seen and respected.

- It strengthens leadership credibility, because a project manager who closes well builds goodwill, making it easier to re-engage people on future projects!

Even small gestures can make a big difference.