Learn when to end a project early, avoid wasted effort, and make confident decisions that protect value and team morale.

In 1785, in a work titled “To a Mouse,” the poet Robert Burns warned “the best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft a-gley.”

You don’t have to understand Scottish dialect to know he wasn’t assuring the mouse that its plans were certain to win it a life of comfort and fine cheeses.

Dean Koontz, Quicksilver

Key terms

Sunk cost fallacy: Continuing a failing project just because time or money has already been spent on it.

Terminate: To formally stop a project with no intention to continue delivery.

Reboot: To restart a stalled project with revised baselines, plans, or leadership.

Salvage: To scale back a project and deliver a reduced but still usable outcome.

Absorb: To shut down a project as a standalone effort but merge its value into another initiative.

Perpetual closure: When a project never officially finishes and keeps rolling without a clear endpoint.

Starvation: When a project is left to fade out slowly through reduced funding and attention, without formal closure.

Controlled exit: A planned and professional shutdown of a project designed to protect reputation and minimize loss.

Ghost project: A stalled project that still consumes resources but has no clear direction or endpoint.

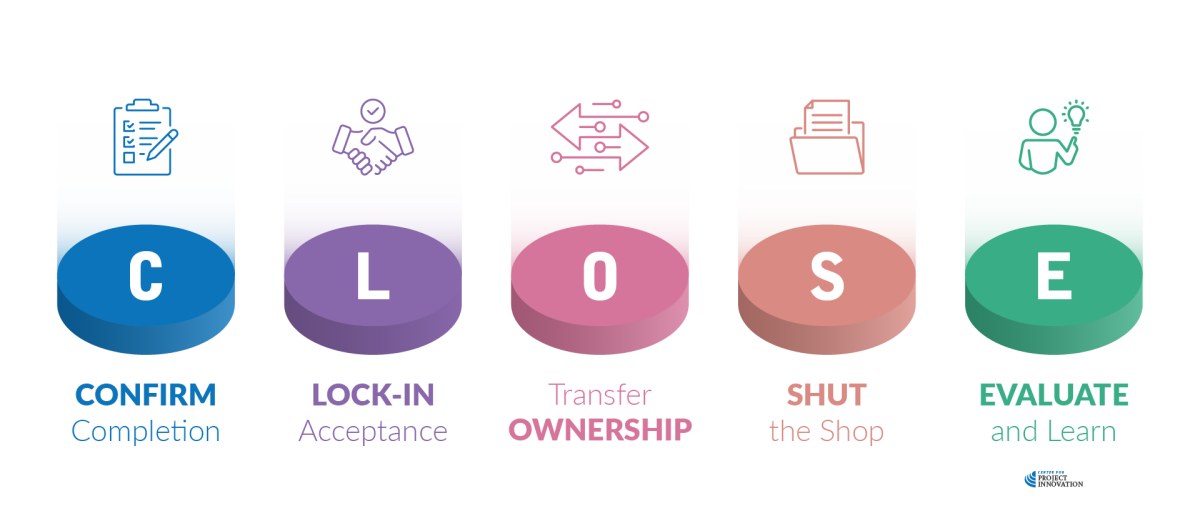

12.1.1: A job well done

Projects successfully close when a few key conditions are met and managed intentionally.

✅ The work is actually finished

The agreed scope has been delivered to the expected quality, without outstanding tasks lingering in the background. Even if the scope changed during delivery, what was finally agreed is complete and accounted for.

✅ The client or sponsor formally accepts the outcome

A project isn’t truly closed until the person or group who commissioned it signs off and confirms they consider the work complete. This involves a clear acceptance process rather than an informal “that’ll do” ending.

✅ Handover to operations or the end user is prepared and supported

The outputs of the project are ready to slot into real use. That means documentation, training, access, instructions, or maintenance plans are in place so the project’s outputs don’t just sit idle after completion and outcomes are never realized.

✅ Close-out activities are completed

This includes final reporting, financial reconciliation, release or reassignment of resources, closing contracts, and capturing learnings. Many projects fail to close on paper even after delivery because this last stretch is neglected.

✅ Lessons are identified and learned

The team takes time to review what worked and what didn’t so that future projects benefit from the experience, leveraging successes and avoiding a repeat of mistakes.

When these conditions are deliberately managed—rather than assumed—the project ends cleanly, the organization can realize the benefits of the work, and the project team can move on without loose ends or ongoing drag.

But what if these conditions are not (or cannot) be met?

12.1.2: The best laid schemes

Despite our best intentions, there are also times when projects just don’t work out.

Commitment to the original vision fades, resources become impossible to pull together, or requirements become locked into a death spiral of non-commitment and unwillingness to move forward.

When this happens, you’re looking at a failed project.

Nevertheless, it is your responsibility to recognize what has happened and recommend the best course forward.

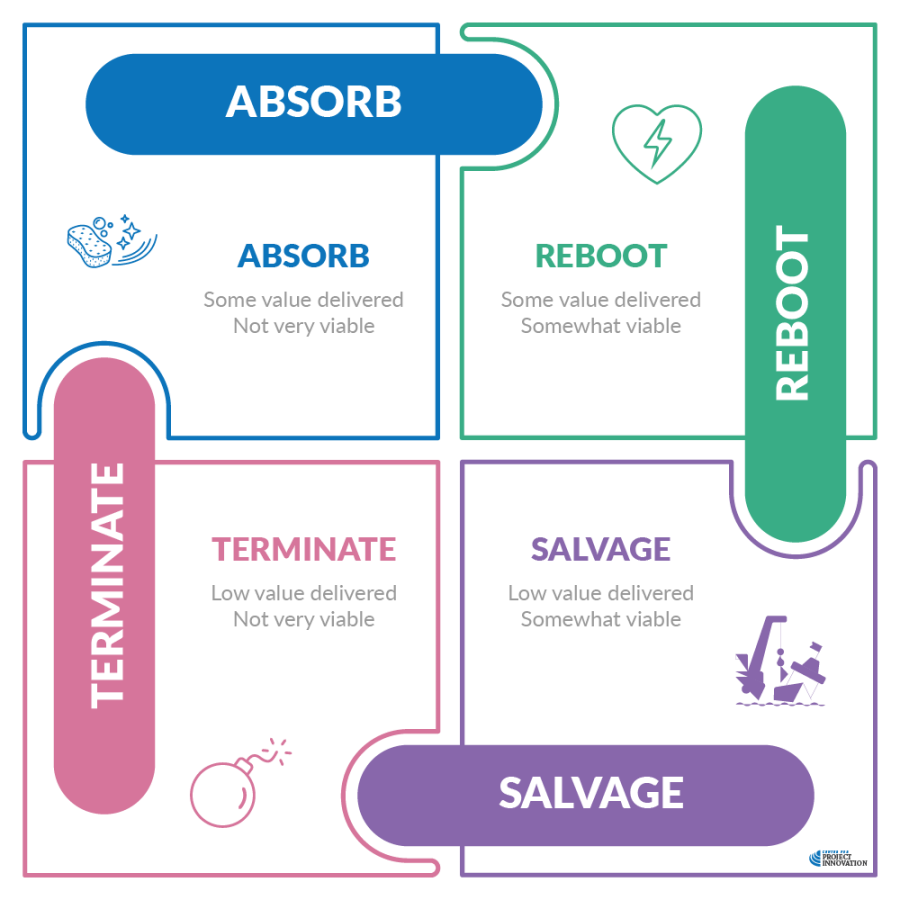

Generally, there are four options that can be explored.

TERMINATE

This is the scorched-earth option for projects that have not delivered any recoverable value to this point and do not have realistic prospects for success (in other words, the project is not particularly viable).

If there is no hope of getting the project delivered, or if the business is so disinterested that no further progress is possible, then closing the project may be the best course.

You should also consider terminating a project if the only justification for continuing is that you have already spent so much time and/or money on it.

This is known as the sunk cost fallacy.

Apple’s AirPower Wireless Charging Mat

Announced with major fanfare in 2017, AirPower was supposed to charge multiple Apple devices at once. After multiple delays and technical problems (mainly overheating and compliance issues), Apple made a rare public admission: the product would never ship.

The project was terminated before launch, even after an estimated acquisition, tooling and marketing spend of over $150 million (about the same they lost on Project Lisa).

REBOOT

Some failing projects, on the other hand, are on the path to achieving their promised value and are still viable; however, other factors—such as personnel issues or external challenges—are frustrating project performance.

In these circumstances, a reboot might be in order.

That said, restarting the project to deliver what was originally set out to do requires more than dusting off the project plan and restarting work.

Often this involves revisiting the business case and creating new baselines predicated on the existing work.

This will require a detailed analysis of the remaining WBS tasks and whether resources need to be re-engaged, contracts renegotiated, or the project schedule reworked.

Quite often, this process starts with a new project manager or team members, recognizing the value that fresh eyes can bring to a stalled project.

Usually, such project managers are the more experienced campaigners in an organization, as the level of skill required to successfully reboot a project is significant.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope

Originally launched as a $1 billion project with a 2011 delivery date, it was plagued by overruns and technical failures.

Rather than abandon it, NASA paused, brought in new leadership, reset the budget and timeline, and essentially rebooted the program with fresh baselines.

It eventually launched successfully in 2021, but only after a complete strategic restart.

SALVAGE

Somewhere between the two lies this option.

Salvaging (also called managing to a profit) is a term we use to describe delivering a project that has less value than was originally planned, but at least offers to provide some benefit from what has been done.

In effect, a new project has been created with new (reduced) requirements, schedules and budgets to give the organization some business benefit, albeit less than originally intended by the business case.

The game Cyberpunk 2077 began as an ambitious project promising a revolutionary open-world experience across all platforms. However, as development progressed, it became clear that the full scope couldn’t be delivered—technical failures, hardware limitations, and missed milestones made the original vision unachievable.

Rather than terminate or reboot, they cut scope and shipped a reduced version of the game. Key features like advanced AI systems and multiplayer plans were dropped, and the focus shifted to delivering a functional core product that could be stabilized post-launch.

Through continuous patches and limited expansions, the company recovered value from a compromised release. It wasn’t what was promised—and stakeholder expectations needed to be appropriately managed—but a standalone deliverable with partial return on investment was achieved.

ABSORB

Absorption happens when an organization decides that while a project can’t stand on its own anymore, parts of it—the technology, team, branding, or infrastructure—are still valuable in other ways.

Instead of terminating it entirely or rebooting it as a standalone initiative, the organization merges it into a stronger or more strategic project, allowing its assets to live on under a different banner.

The Fire Phone failed commercially and was pulled from sale, but instead of simply junking everything, Amazon absorbed its voice recognition tech, user interface experiments, and hardware teams into the newly emerging Echo/Alexa ecosystem.

The standalone project died, but its DNA lived on in one of Amazon’s most successful product families.

Closing an unsuccessful project doesn’t always mean pulling the plug. It’s about making intentional decisions to either end it cleanly, restart with clarity, recover some benefit, or roll it into something more viable.

Clearly, you, as the project manager, cannot make the decision about which option to pursue—that falls to the sponsor and/or client.

You can, however, recommend and guide and advise.

A project manager faced with this situation—whether on a project they started or inherited—should have the confidence to work through and present these options, and then deliver on whichever is selected.

12.1.3: What if we just keep going?

Not making a clear decision about a struggling project can be more damaging than terminating it.

When a project is allowed to drift without direction, it enters one of two states—perpetual closure or starvation—both of which consume resources quietly while delivering diminishing or even negative value.

Perpetual closure

In this state, the project looks active on paper but never actually reaches completion. Scope continues to shift, stakeholders add more features, and no one declares an endpoint.

- In Agile environments, ongoing iteration can be appropriate when it’s tied to continuous delivery of value.

- In predictive environments, this behavior becomes a trap. Planned outcomes are never formally closed, and finalization tasks like documentation, handover, and sign-off are repeatedly delayed.

This leads to fatigue, budget creep, and declining morale because nobody knows when “done” actually is.

Starvation

Starvation happens when a project isn’t officially closed but is slowly stripped of funding, attention, or resources. There is no formal completion, no communication to stakeholders, and no official sign-off. Work slows, decisions stall, and the project quietly fades into the background.

- Resources are still being consumed, just at a slower rate.

- Stakeholders assume progress is being made because nobody has declared otherwise.

- The organization ends up carrying a “ghost project” that blocks capacity without delivering value.

Both scenarios occur (sometimes simultaneously) when leaders avoid making a firm call.

The solution lies in structured stakeholder communication and change management. If a project needs to shift direction, scale back, or stop, it must be done formally and transparently—not by silence or endless extension.

Failing to make a decision is still a decision. It’s just the least controlled and least strategic option. A confident project manager recognizes this and leads stakeholders toward clarity rather than quiet decay.

12.1.4: The courage to quit

When a project no longer makes sense to continue, the project manager’s role shifts from delivery to protecting organizational value, even when that means speaking an uncomfortable truth.

A project becomes a candidate for early closure when:

- Objectives can no longer be met, even with extra effort.

- Cost to complete has overtaken expected value, as originally outlined in the business case.

- The business environment has shifted, and the original need has diminished or disappeared.

This is where our change management process becomes more than paperwork.

A strong change control process forces stakeholders to revisit the business case, check that assumptions are still valid, and make decisions based on current reality—not past commitment.

This step is what stops good money from going after bad.

The role of the project manager

You are often the first to see signs that a project is no longer viable. Like a canary in a coal mine, your insight comes from being closest to the work. This means you may need to:

- Raise concerns early, before failure becomes irreversible.

- Trigger a formal review, rather than relying on informal conversations or hope.

- Bring stakeholders back to the original success criteria and benefits outlined in the business case, asking: “Are these still achievable? Are they still even relevant?”

That said, calling attention to a struggling project can feel risky. It often requires courage to start difficult conversations, especially when stakeholders are emotionally or politically attached to the original vision.

True project leadership involves speaking plainly about:

- The team morale and organizational reputation risks of dragging out a failing project.

- The regulatory, legal, financial, and stakeholder liabilities if the project continues without a clear return on investment.

- The reality that closing a project still costs money, so the exit must be intentional to avoid unnecessary damage.

A controlled and transparent closure can still deliver value through things like documentation, partial deliverables, or lessons learned.

More importantly, it protects credibility. A well-run termination framed around responsible use of resources can strengthen trust more than a slow, silent decline.

You should ultimately use the business case as the anchor point. Ask:

“If this project were proposed today—based on current costs, priorities, and risks—would we approve it?”

If the honest answer is no, then continuing is just prolonging the fruitless expenditure of time and resources that could be more productively spent on other things.

Courageous quitting is not a failure of delivery. It is a success of governance and leadership, proven by the willingness to make a tough decision before more damage is done.