EAC and ETC

Using your earned value data, you can now forecast an estimate at completion (EAC) based on the project performance.

This may differ from the budget at completion (BAC) originally planned.

It is especially important to develop an estimate at completion (or an estimate to complete (ETC) the remaining work) if it becomes obvious that the BAC is no longer viable.

Essentially what we are doing here is updating the estimates (or planned value baseline) made in the original project plan to more accurately reflect the real-world circumstances of project delivery.

There are a few ways you can do this.

BOTTOM-UP EAC

Have you ever got halfway through a shopping trip, realised you are likely to overspend your allowance, and readjusted your budget to suit the circumstances?

The bottom-up EAC method takes the actual costs and experience incurred for the work completed and requires a new estimate to complete the remaining project work.

In other words, it is the sum of the actual costs to date, plus a fresh estimate of what it will take to finish.

For example, if our project has spent $120, and the project team estimates it will take another $70 to complete the work, then our new estimate at completion, or EAC, is $190.

Simple, isn’t it?

Note that this method is not an excuse to guess; rather, it relies on the original estimation techniques we described in the previous two Modules.

Importantly, you do not need any earned value management data beyond an appreciation of actual costs and earned value to perform a bottom-up estimate to complete.

This method is problematic, however, in that it interferes with the conduct of project work.

The personnel who are performing the project work have to stop working to provide a detailed, bottom-up ETC of the remaining work.

Typically, there is no separate budget to perform the ETC, so additional costs are incurred while it is in progress.

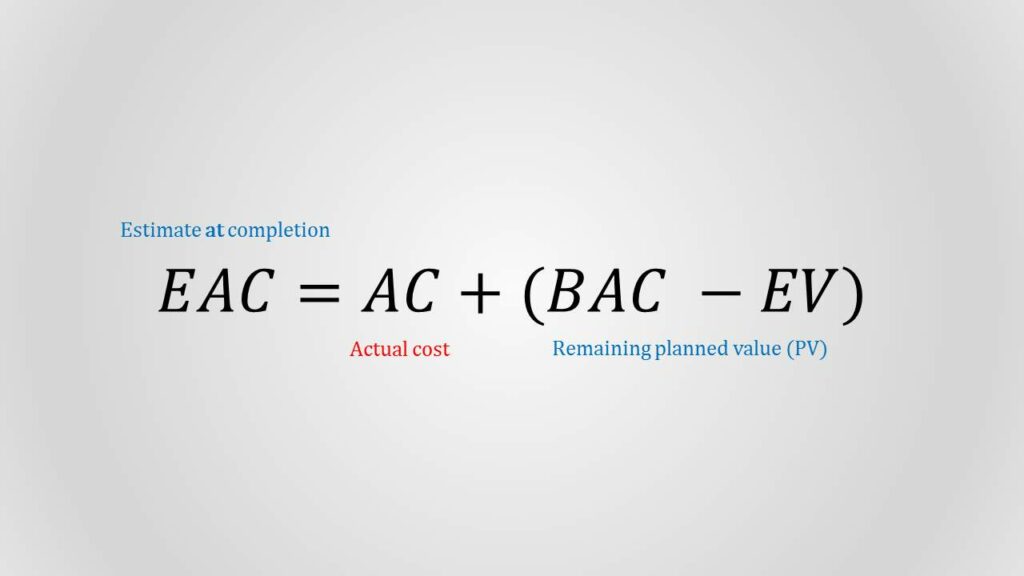

EAC USING PV

This method accepts that the actual project performance to date (whether favorable or unfavorable) is accurately represented by the actual costs.

However, it predicts that all future work will be accomplished at the original budgeted rate (our planned value).

Therefore, if a project has actual costs of $120, a budget at completion of $100, and an earned value so far of $50 (50%), our new estimate at completion will be $170.

This is because we have forecast that the remaining work will remain true to the original budget and only the balance of $50 outstanding is required.

This method may be applicable when a significant, one-off event distorts the budget but is unlikely to impact future delivery now the event has passed.

For example, start-up capital costs may have been much higher than anticipated, but now the project is using the equipment as predicted, and no future variation is likely to occur.

Nevertheless, when actual performance is unfavorable, the assumption that future performance will return to normal should only be accepted when supported by your risk analysis.

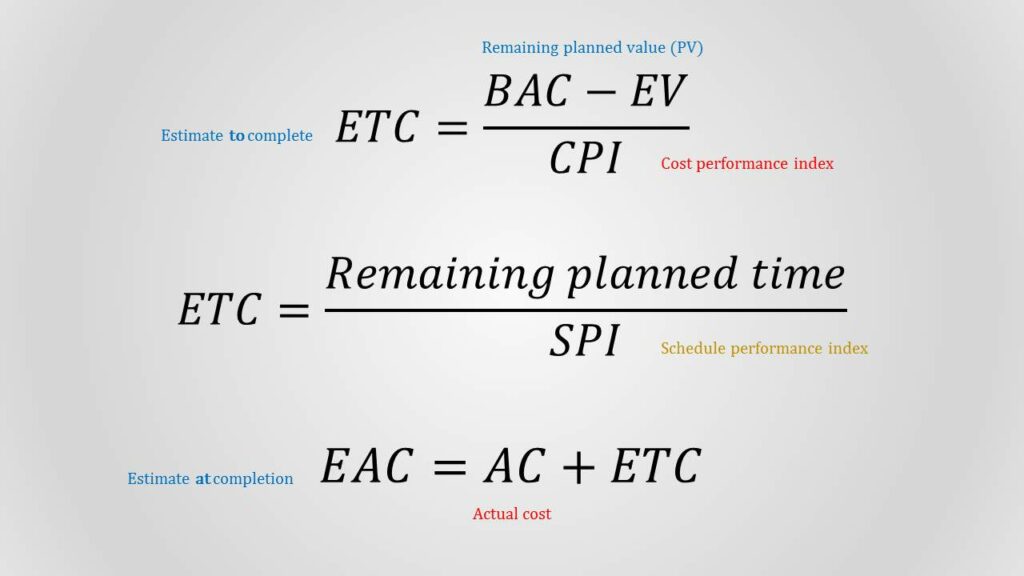

ETC USING CPI / SPI

By applying the CPI or SPI to the remaining work, we can extrapolate how much more time or money the project will need from now.

Our assumption here is that whatever caused our change in schedule or budget is likely to continue to impact the rest of the project.

For example, a project scheduled to finish 15 weeks from now with an SPI to date of 1.2 could be reasonably forecast to finish in 12.5 weeks – if the factors that led to the original schedule variance are expected to continue unchanged.

Similarly, if our project has a CPI of 0.8 and a remaining PV of $5,000, then applying the same logic, we will probably need $6,250 to get the remaining work done.

In other words, as per the formula below, you divide the balance of the work required by the relevant index (CPI or SPI).

At this point, you can also add the actual cost (AC) to date to the ETC to arrive at your new EAC.

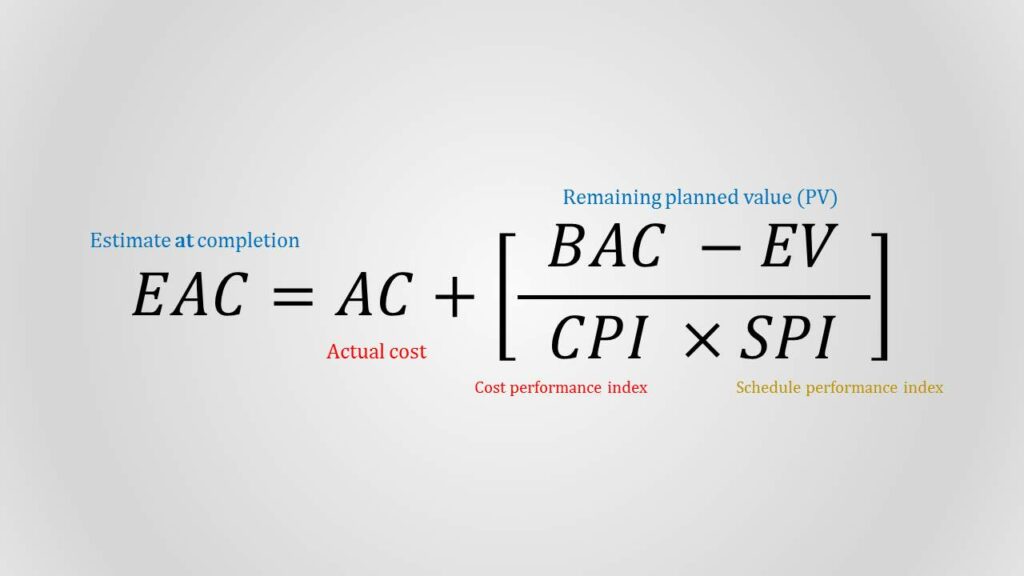

ETC USING CPI & SPI

The final forecasting method uses the equation below to forecast the ETC work considering both SPI and CPI factors.

As you can see, this method essentially converts the two previously described approaches into a single equation; however, it is slightly less robust as the outcome is inevitably expressed in a dollar value that may not perfectly reflect either actual costs or time.

It is nonetheless useful for inter-project comparisons.

Variations to this method might weight the CPI and SPI at different values (for example, 80/20, 60/40, or some other ratio) according to the project manager’s judgment.

What happens next?

Each method can provide the project management team with an ‘early warning’ signal if the SPI or CPI returns are not within acceptable tolerances.

You might also run the most appropriate statistical method alongside a manual, bottom-up estimate for completeness.

A range of calculated EACs might further be prepared to represent various risk scenarios.

Note that because the estimate to complete (ETC) becomes our new baseline – replacing the original planned value (BAC) – you should again consider the timing of costs if they will significantly impact on the new plan.

Also, update the tolerances and control limits to reflect the new reality.

Forecasting how much it will take to complete the project work, and using this to determine a new project baseline, allows us to realistically provide for issues that arise during the delivery of the project.

This might include drawing down on contingency reserves if the issues were foreseen as risks, or management reserves if not.

Other responses might be renegotiating the schedule or budget with stakeholders.

The best formula for any given scenario depends on the ability of the project manager to consult with stakeholders as to the cause of variable performance, and determine whether or not the event is likely to impact downstream performance.

Finally, even though you might set a new budget or schedule as a result of your forecasts and monitor and control future performance against that baseline, it is essential that you also reference the original budget when you ultimately review the project to identify any lessons that could be learned.