Risk tolerance

When is a risk not a risk, but something the project can live with?

The terms risk appetite and risk tolerance refer to the degree of uncertainty someone is willing to accept, usually in anticipation of a reward.

For example, fast-tracking a project’s schedule is a risk often taken to achieve the reward created by an earlier completion date.

Individuals and groups adopt attitudes toward risk that influence the way they respond.

These risk attitudes are driven by perception, tolerances, and other biases, which should be made explicit wherever possible.

The problem, though, is that organizations and stakeholders all have varying degrees of risk that they are willing to accept.

Complicating this further, projects are, by their very nature, riskier undertakings than business-as-usual; therefore, the default risk settings of an organization need to be adjusted to accommodate the risk/reward trade-off introduced by projects.

A consistent approach to risk should, therefore, be developed for each project or program of work, and communication about risk and its handling should be open and honest.

Probability/impact matrix

The probability/impact matrix is a popular risk management tool common to projects and business-as-usual.

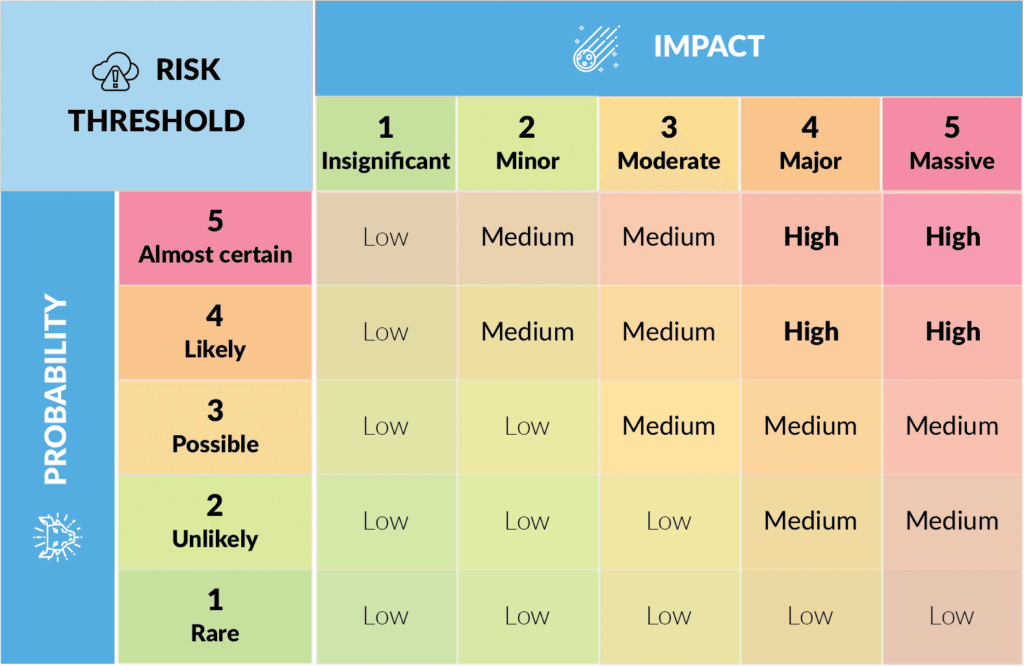

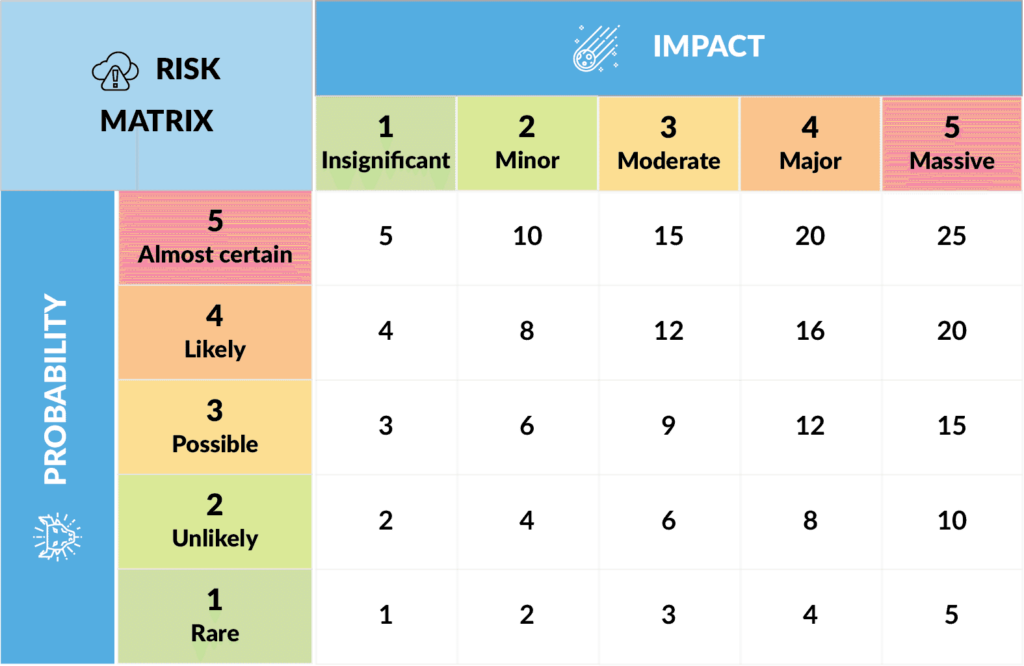

Although it is commonly used as a ready-reckoner for calculating a risk event score (as we did in the last topic), its more important function is to set the organizationally agreed risk thresholds for each project.

In this example, the risk thresholds for the project are set at low, medium, and high, where any risk with a rating from 8-15 is considered to be a medium risk, and risks scoring above or below that band would be high or low, respectively.

So, continuing our previous example, with a score of 12, damaging an iPad would be considered a medium risk, whereas landing Ryan Gosling only rated a 5, and would be considered a lower priority opportunity.

Response strategy

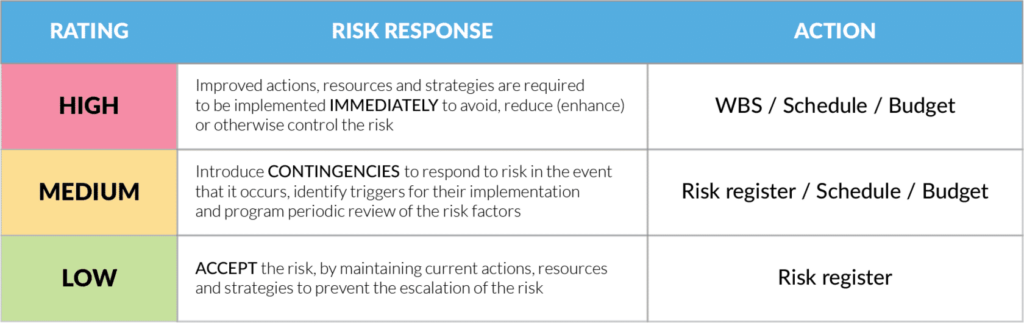

Just calling a risk low, medium, or high adds nothing to the project unless there is an action linked to it.

That is why the response at each threshold needs to be clearly defined and consistently applied.

The following table illustrates this:

For this project, high risks require immediate action.

We must insert something into our project plan that says we will do X to ensure the risk either does not occur, is less likely to occur, or if it does occur, doesn’t impact us as badly as originally foreseen.

This necessarily involves creating a new task or group of tasks in our WBS, each needing to be costed and similarly inserted into our schedule.

A medium risk, on the other hand, requires us to establish a contingency.

A contingency is an action that is only exercised if the risk eventuates (becomes an issue).

For example, because our iPad might be damaged, we can set aside the price of a replacement iPad in our budget so that we have the money available to purchase a new one if required.

The float in your schedule can also be used as a contingency if required.

Because you can set aside either time or money as a contingency, the schedule and budget need to be updated accordingly.

We will discuss contingency planning in much greater detail shortly.

You should also monitor this risk to see if the risk does materialize or if its circumstances change.

The document we use to manage this is called a risk register – again, we will discuss this in more detail soon.

Finally, a low risk is one that we accept.

In doing so we acknowledge and monitor the risk in our register, but do not take any action or allocate any allowances to it unless circumstances change so as to escalate it to a higher threat level.

With the finite time and scarce resources available to projects, we do not have the luxury of thoroughly treating every little risk as you might do in an operational setting.

That said, it is important that you carefully set your thresholds and related actions at levels that align with the expectations of stakeholders and the risk appetite of your organization.