A momentary lapse of reason…

Under the noontime sun of New York’s first day of summer, Snapple, the soft drink maker, answered the question of whether a 17½ ton popsicle can be made to stand upright in Union Square.

Apparently, it cannot.

As it turned out, the two-and-a-half-storey tall frozen treat melted much faster than the organizers anticipated, flooding downtown Manhattan with kiwi-strawberry-flavored goo.

Cyclists wiped out in the stream of slush. Pedestrians went belly-up. Traffic was, well, frozen.

Firefighters were forced to close off several streets and use high-pressure hoses to wash away the thick, sweet slime.

Now you might have thought that this was a fairly foreseeable risk, but it shows that merely identifying the risk is by no means the end of the risk management process.

Qualitative vs. quantitative risk analysis

There are two ways to analyze risks: qualitatively and quantitatively.

Quantitative risk analysis is a technique that uses statistical methods to illustrate the relationship between each risk and the project. We will return to it shortly.

Qualitative risk analysis, on the other hand, involves making judgment calls regarding the probability (or likelihood) of an event occurring versus its potential impact (or consequence).

In qualitative risk analysis, we assign relative values to a risk’s cause and effect.

We can determine these values by referencing similar projects or events – in other words, an analogous estimate – or by getting consensus among stakeholders.

Occasionally we can be quite precise in our estimates of probability by using, for example, a statistical technique that lets us determine a 37% likelihood that an event will occur.

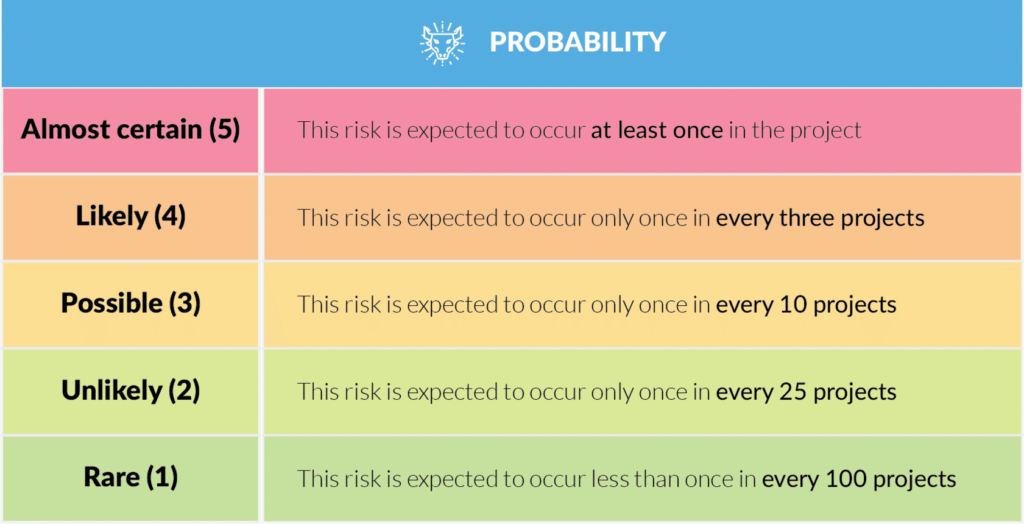

More often than not, though, we assign a probability score on a scale from one to five, where one represents a very low probability of the risk occurring, and five indicates that it is very likely.

But what does that mean?

To me, a ‘very likely’ event might occur daily; whereas you might rate something as very likely if it happens every month.

We therefore need a standardised definition …

Defining probability

In the table shown here, probability is much more clearly defined.

Even though there is still an element of subjectivity (and potential stakeholder argument) as to whether or not a risk may occur once every 10 or 25 projects, when consensus is achieved, what we mean by ‘possible’ or ‘likely’ is commonly understood by all.

It should finally be noted that the same risk will have different probabilities on different projects and should be independently assessed.

For example, there might only be a low probability of rain disrupting a one-week tennis tournament. In contrast, the likelihood of rain (the exact cause) interfering with a 12-month construction project will be quite high.

For this reason, we can never perfectly cut-and-paste our risk analysis from one project to the next, a lesson that applies equally to our assessments of impact.