Top-down v bottom-up

In the last Module, we discussed the estimation principles as they apply to the business case.

As indicated at the time, all those methods can be applied with equal rigor to the project planning phase.

Now we have adopted the preferred alternative as our project, we need to sharpen our estimates from a plus-or-minus 20 percent margin of error to get within 10 percent of what our actual costs might be.

How do we do that?

The method we applied in the business case was what we call a top-down estimating technique.

In other words, we looked at the project as a whole and asked how much would this output typically cost, and how long it would take to deliver, if (for example) we purchased it on the open market.

Bottom-up estimating, by contrast, takes that bottom line of the WBS – the tasks at their finest level of detail – and asks how much each of these elements will independently cost, and how long they will take to deliver.

Because we are estimating the discrete units of cost and time and adding them together (or ‘rolling them up’ as it is sometimes known), we can be confident that our total estimate of project cost and time will be much more precise.

Analysing requirements

To make accurate estimates for our project budget, we need to first ascertain what the resource requirements are for each task.

This process is properly known as requirements analysis, although that term can also be applied to the entire WBS / scope definition process (as we have done in this Unit).

In requirements analysis, we ask, what do we need in the way of:

- Equipment?

- Materials?

- Labor?

We can consult Google, expert stakeholders, or past project reports to get this data.

We can also apply analogous, parametric, or other statistical techniques to fine-tune our estimates.

When analyzing our labor requirements, we also need to understand:

- How much each unit of labor costs (for example, $50 per hour)

- How many direct hours of labor are required (for example, 5 people x 2 hours each x $50 per hour = $500), and

- How long it will take to complete the task (for example, 3 weeks)

Note the difference between labor cost and time to complete.

Just because it takes 10 hours of effort to deliver a task doesn’t mean you will receive the output exactly 10 hours after work starts.

More often than not, our dependency on other activities (such as staff availability and delivery times) necessitates wait time in our schedule.

Although the time to complete is not required for our project budget, it is a vital input into our project schedule, which we shall look at shortly.

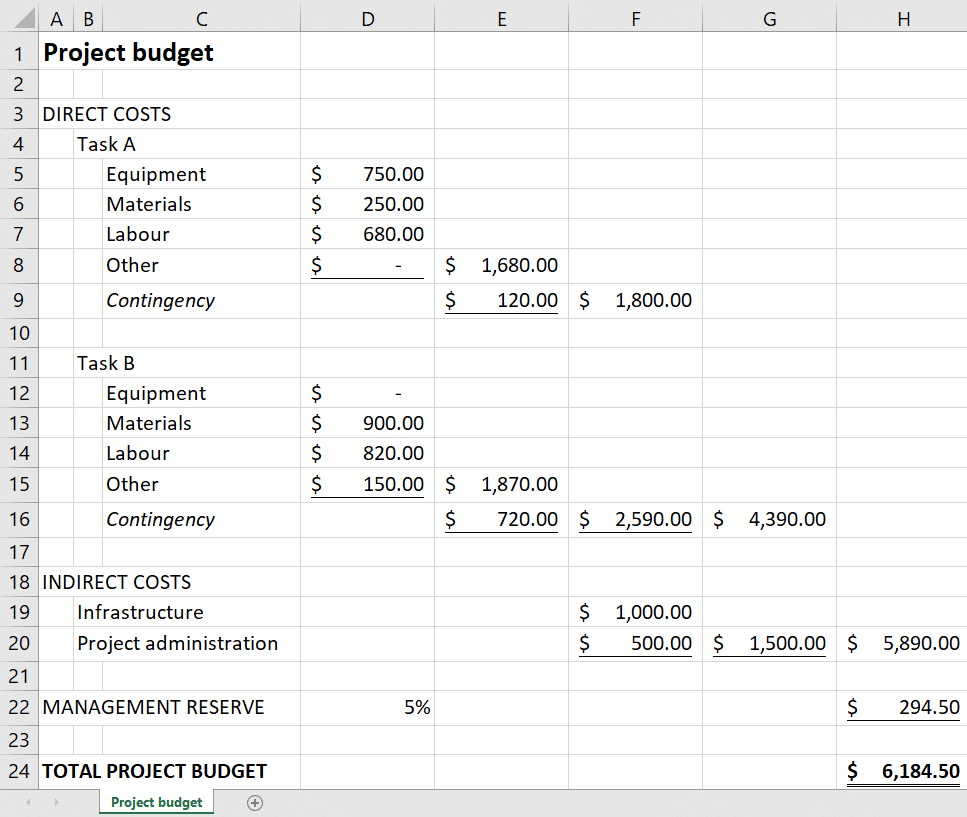

The total (budgeted) cost of each task is therefore:

Equipment + Materials + Labour + Other Direct Costs

Contingency reserves (which we will introduce in the Unit on Risk) can then be appended to the budget for each task.

Indirect costs and management reserves (also discussed in that Unit) are applied to the overall project budget.

Note that equipment (or other resources) shared over multiple tasks are also usually entered as indirect costs.