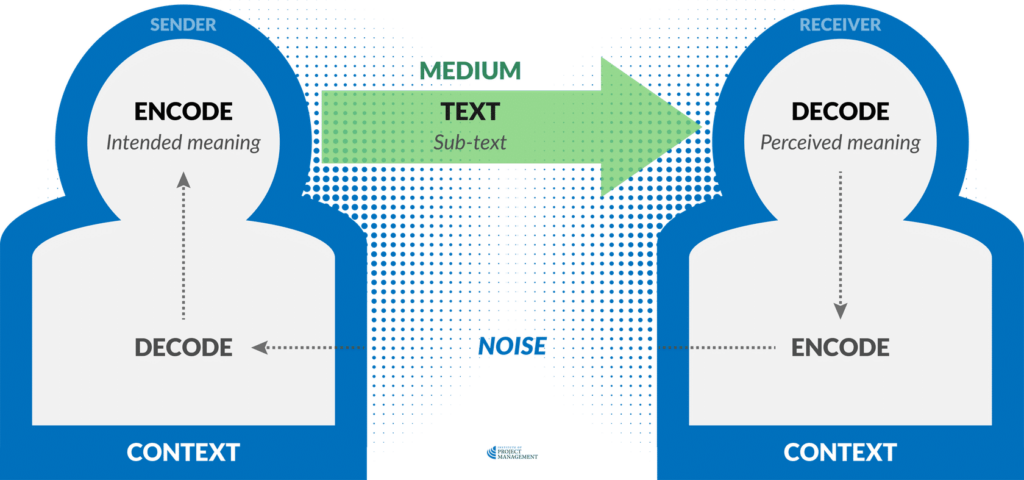

Every communication requires a sender and a receiver.

The sender takes the information they wish to communicate and encodes it in their preferred medium.

Encoding is the process of composing your message as a verbal or written statement.

That statement can then be transferred into and channeled through any variety of media, including over the telephone, in an email, as a written report, or a project plan.

Sub-text in verbal communication includes paralinguistics (speed of voice, intonation, tone, volume, articulation, pronunciation etc) and body language.

Sub-text in written communication includes formatting, font, tone, punctuation, images, emoticons, and the like.

On the way to the receiver, the message is subject to noise.

Noise, in this instance, refers to anything that might interfere with the transmission and decoding of the message by the receiver.

It can be literal noise (for example, speaking on a phone while riding a noisy train) or figurative noise, such as a distraction or even an absence of something, such as a lack of background context for the message.

Context is also situational and unique to each communication. It is the sum of each party’s:

- National, familial, social, and workplace cultures

- Lifetime experiences (up to and including your experience with the party or parties you are communicating with)

- Personality – how you typically behave

- Mood – how you feel in the moment

If people do not understand why a message is being sent, or the broader circumstances it is alluding to, then receivers are likely to decode your message in totally unanticipated ways.

Inherent in the model is an action to acknowledge a message.

Acknowledgment, however, only means that the receiver signals receipt of the message – it does not imply agreement.

The final action is the response to a message, which means that the receiver has decoded, understands, and is replying to the message.

The sender is therefore responsible for making the information clear and complete so that the receiver can receive it correctly, and for confirming that it is properly understood.

The receiver is responsible for making sure that the information is received in its entirety, understood correctly, and acknowledged.

So, how does knowing this make you a better project leader?

Each of these transaction points represents a potential for communication failure – it is a wonder we can communicate at all!

Ultimately, the model shows the importance of clarity in communication.

Each element represents a point at which the communication could be distorted or fail.

You should always keep your messages simple and easy to understand, staying mindful of the context they exist in and the noise that might disrupt them.

More importantly, being an effective communicator depends as much on your ability to listen as it does on your ability to talk or write.

This is something we will explore in more detail further in this Unit.

Effective and efficient communication

Given the constraints on a project manager’s time, their goal should be to communicate as effectively and efficiently with stakeholders as possible.

Effective communication is providing information in the right format, at the right time, and with the right impact.

This does not mean, however, that things only ever need to be communicated once.

Redundancy – the need to repeat and reinforce messages – may be necessary if a message needs to be widely broadcast and/or is highly critical.

Reactively redundant managers pester team members after the event with increasingly irritating messages via the same channel.

For example: once a milestone is missed, the reactively redundant manager begins sending daily emails asking for information.

Good project leaders are proactively redundant when communicating – they repeat and reinforce key messages using multiple channels in anticipation of an event or requirement.

For example: a phone conversation is followed up with a confirmatory email, and a quick text message to check-in in the lead-up to a deadline.

Efficient communication refers to finding the balance between under- and over-communicating information.

Under-communication

Cast your mind back for a second to the power / interest matrix – what risk do you see in under-communicating (not telling enough) to our highly powerful and interested stakeholders?

Aristotle once stated that nature abhors a vacuum. In physics, nature contains no vacuums because the denser surrounding material would immediately fill the void.

In our setting, the absence of information (under-communication) will often lead to stakeholders making unsupported assumptions and leaping to erroneous conclusions about your project.

They also tend to ‘worst-case’ scenarios, assuming that you would have told them if there was good news.

The related risk with under-communication is that people will not have the information necessary to make good decisions.

As stated earlier, the more assumptions we use to fill our information gaps, the greater the margin of error (or lesser confidence) we will have in our estimates.

Under-communicate at your peril!

Over-communication

If you are unsure where the balance lies, you should always tend towards over-communication; yet over-communication comes with its risks, too.

In this instance, you may be investing resources (time and money) into communicating things people don’t want or need to know – resources that could be better spent on managing other aspects of the project.

Beyond the obvious risk of annoying stakeholders, you also risk making people blind to your important messages – those you really need them to act on.

Think about your inbox… do you read every word of every message your mother sends you three times a day? Has it ever got you in trouble?

Over-communicating information may also risk inviting input and contributions from stakeholders who have no legitimate value to add.

This can result in you doubling the resources you spend on communication in managing these new expectations.

Err slightly toward over-communication, but don’t over-do it!

Communication complexity

Did you ever play that game where you each take a turn whispering a message down a line of people and hearing how confused it was at the other end?

Well, as a project manager, you should also be aware that the number of potential communication channels or paths is an indicator of the project’s complexity.

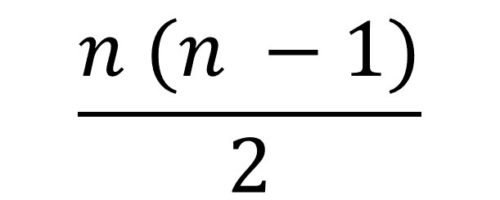

There is a mathematical formula for this (where n represents the number of stakeholders):

A project with ten stakeholders (n=10) has 45 potential communication channels.

A project with 100 stakeholders, on the other hand, has 4,950!

Therefore, as you increase the number of stakeholders, the risk of communication complexity increases exponentially.

Because each channel has its own context, noise, and constraints to dialogue, a key component of project planning is determining and limiting who will communicate with whom, and who will receive what information.

You do this by limiting people’s authority to communicate certain information.

Now, some might see this as a barrier to free speech and the free exchange of ideas and this may be counter-productive from an innovation perspective.

Nevertheless, the opportunity for miscommunication to occur within projects is often under-appreciated, and this can distract from the work at hand and frustrate project objectives.

For that reason, it is vitally important that clear and consistent messages are passed within the team and to external stakeholders, something that is within our ability as project managers to control.