Picking a winner

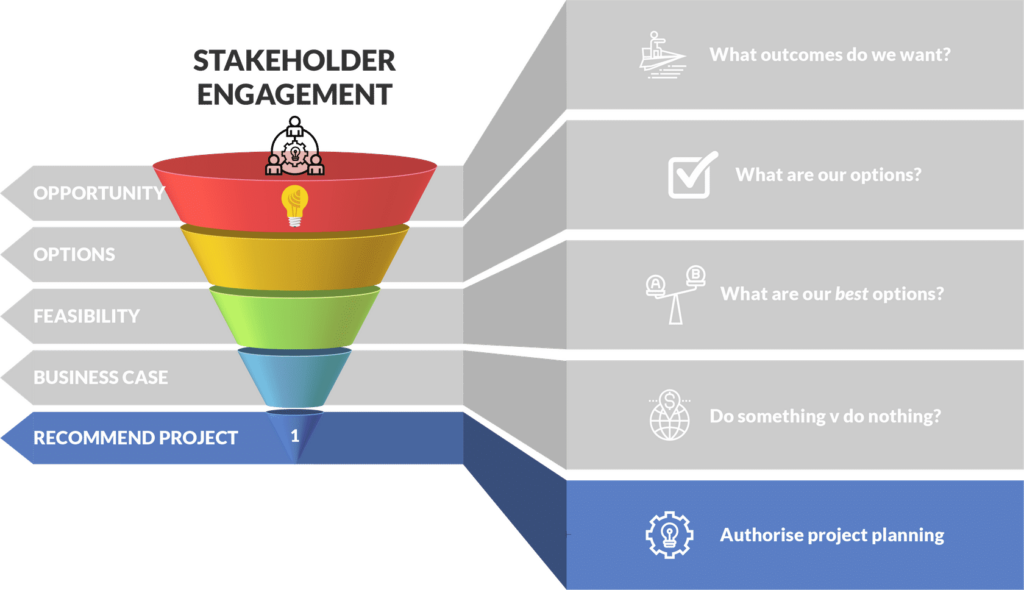

Let’s reflect on what we have achieved to this point.

- Opportunity definition: We started with an idea, visualized its potential, and assessed the risk to the organization of investing it.

- Options identification: We then identified a range of different ways to deliver the same or similar outcomes.

- Feasibility analysis: We reduced these options to two, three, or four high potential projects that could be compared against the base case of doing nothing.

- Business case: We estimated the financial and other impacts of proceeding with each remaining option.

We now need to make a recommendation to our decision-makers on the best option and the way forward.

The good news is, as you can see, the hard work has been done.

All that is left is to summarise our findings in a way that highlights the optimal solution.

To do this, we use a technique called multi-criteria analysis (MCA).

As the name suggests, multi-criteria analysis can include any decision-making factor (or criterion).

When deciding which is the best project option (including the null option), the evaluation criteria might be specific to the outcomes intended by the opportunity.

For example, if the outcomes we desire include:

- increasing market share

- improving customer satisfaction, and

- returning a profit to shareholders…

… then our criteria might explicitly ask to what extent each option increases market share, improves customer satisfaction, and returns a profit.

At a higher level, when we are deciding which projects to add to our portfolio from the recommended business cases, we might have some organisationally predefined criteria, such as:

- Project costs

- Net financial impact

- Other intangible impacts

- Risk to the organization

The purpose of MCA is to give each criterion a score – it can be out of three, five, ten, or whatever scale you like – so that when you add each criterion score for each option, you are left with an obvious winner.

MCA example

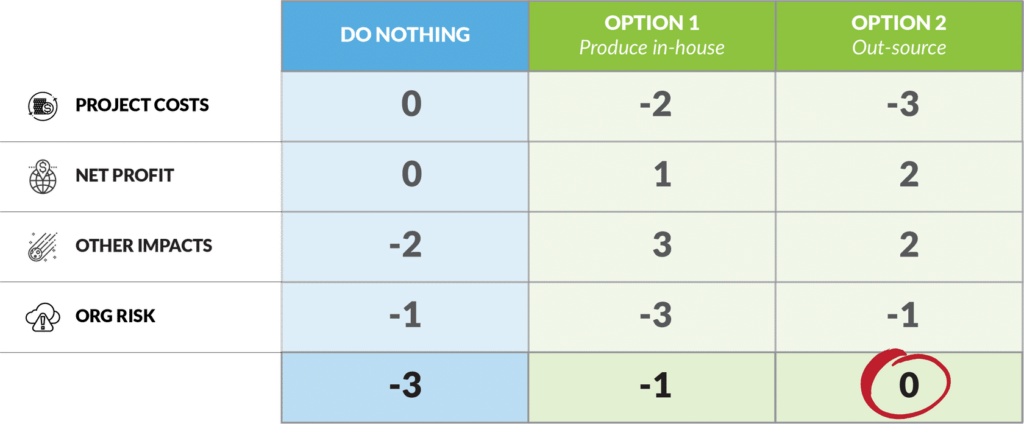

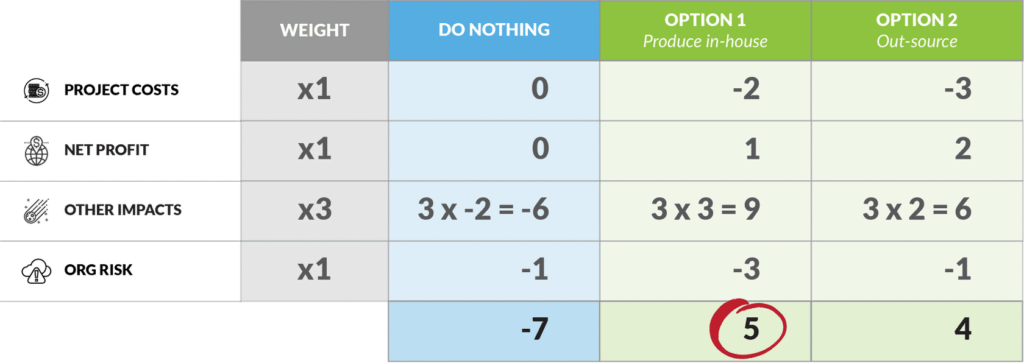

Let’s suppose that we have three project options: do nothing, make something in-house, or outsource production to experts.

Based on our comprehensive analysis of the potential project costs, net financial and other impacts, and the risks to our organization, we have given each option a score out of five for each criterion.

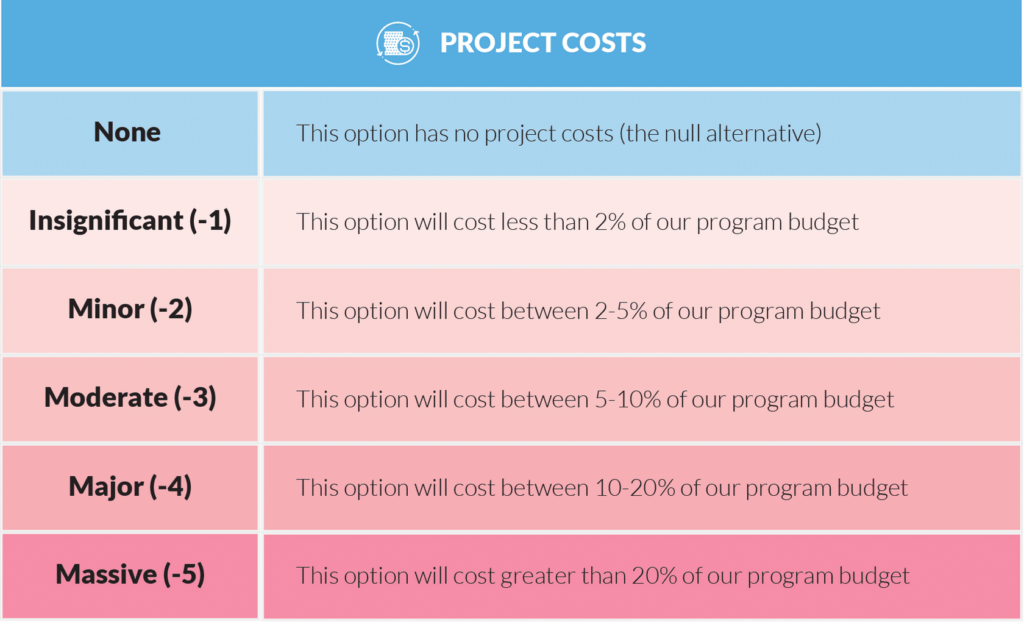

Project costs

If everything else is equal, saving money is better than spending money for an organization. For this reason, expected project costs are assigned a negative score by default.

In this example, outsourcing is more expensive than delivering the project in-house, so it has a larger negative score.

As discussed earlier, though, doing nothing has no project costs, so this option has a default score of zero.

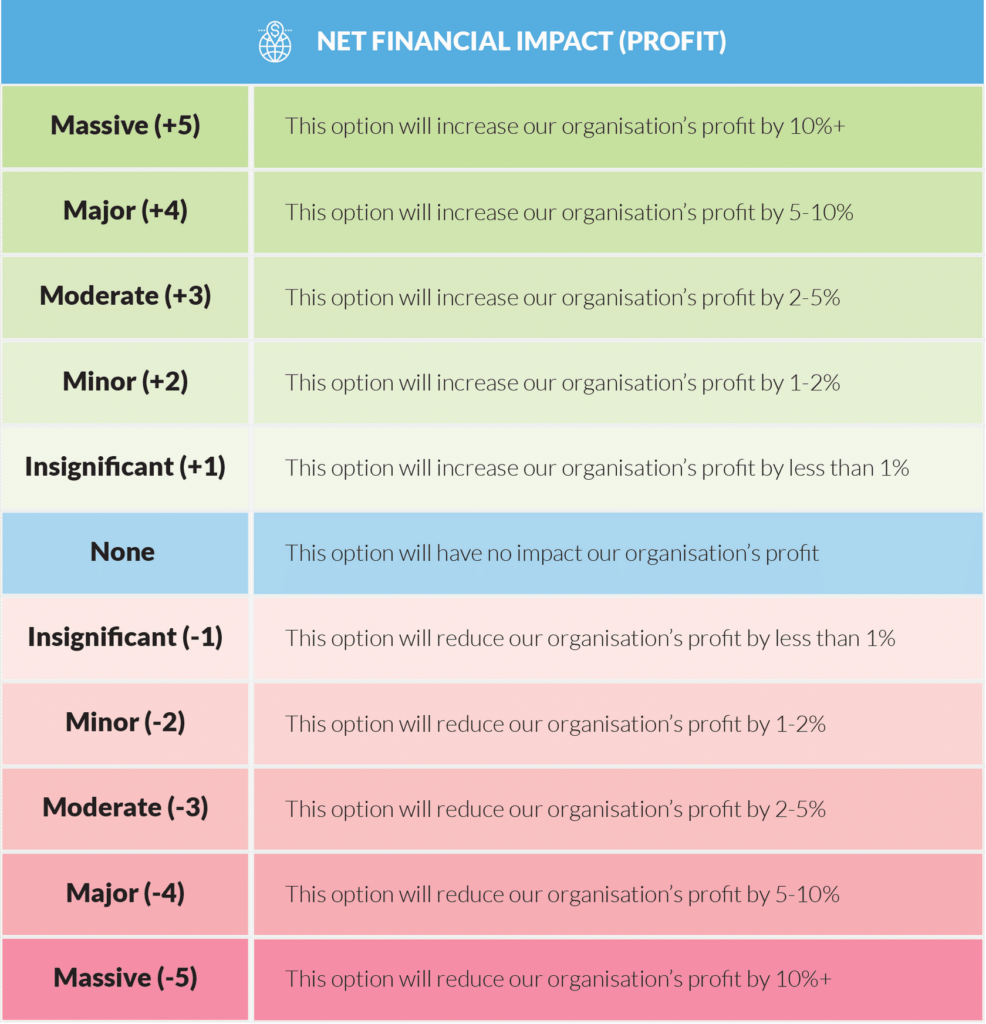

Net financial impact

A net financial impact can be positive or negative, and this is reflected in the score we give.

In our example, both project options are expected to be profitable, so they both receive positive scores. Electing not to pursue this opportunity will have no impact on our profitability.

It can be seen that our business case author believes the outsourced solution will be more profitable than the solution produced in-house.

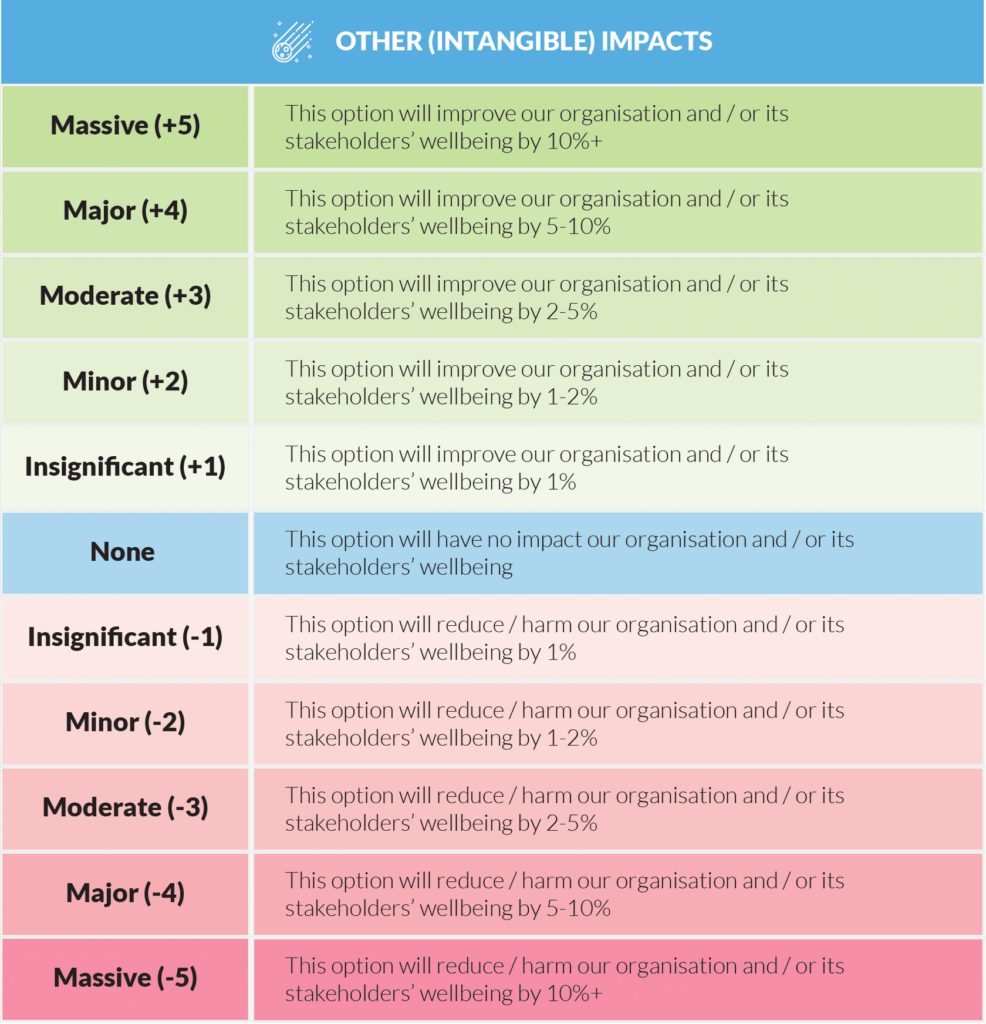

Other, intangible impacts

Here is a more complete illustration of the effect of positive and negative scoring.

We can assume from the scores assigned that doing nothing will, on balance, bring harm to our organization; whereas, proceeding with the project will impact us positively.

We can also infer that delivering our project in-house will provide a more significant sum of intangible benefits than looking to someone else.

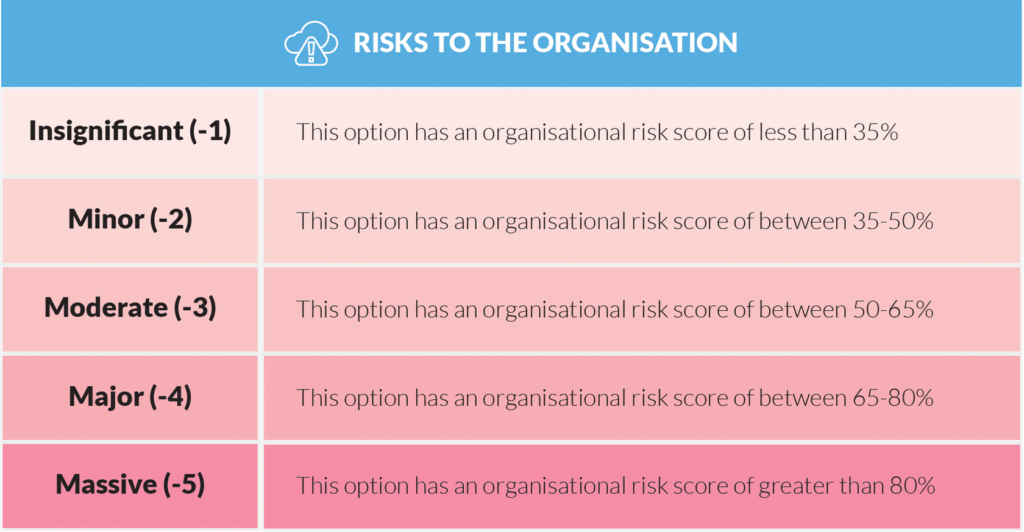

Risk to our organization

Here is another opportunity to use our risk profile tool!

Risk, as we have defined it in our organizational risk matrix, is inevitably negative; therefore, we have converted our percentages from the risk matrix into a range of scores from -1 (being low risk) to -5 (being high risk).

In our example, doing nothing or outsourcing are seen to carry a low level of risk, whereas delivering the project in-house carries a moderately higher risk for our organization.

Recommendation

When we total our scores for each option, we see that do-nothing scores -3 (rank #3), Option 1 scores -1 (rank #2), and Option 1 scores ±0 (rank #1).

Therefore, using these criteria, Option 2 is the best option, and we will recommend outsourcing the project.

Note that the best score is always the highest raw score – even if all the totals are negative, the top-ranked option may be worth proceeding with.

That said, your organization may have a policy that only business case options with a positive score will proceed.

It is essential to get stakeholder consensus on what appropriate scores might be, and be able to explicitly justify them when called upon to do so.

Indeed, good practice suggests that you should have clear definitions for each score and apply them consistently when preparing your MCA.

As always, the criteria and definitions proposed here are intended as examples only; you should update them to reflect the unique circumstances of your project and organization.

You should also beware of double-counting criteria.

For example, if you include project costs as a distinct criterion for business case decision-making, you should exclude those same costs from your analysis of risks to the organization.

In the same way, project costs should be excluded from your net financial impact formula if you are separately evaluating the impact of outputs and outcomes (as we have done in this example).

Weighted MCA

Multi-criteria analysis is all well and good, but in its most basic form, it can be something of a blunt instrument.

Sometimes, a more sophisticated approach is called for…

Let’s suppose that our organization is a government or not-for-profit agency.

As such, it is more important to us to have a positive impact on the community than it is to make a financial profit.

How might these circumstances impact the decision we just made in our example?

In this instance, our organization might weight each criterion to reflect its priority to us.

Using these conditions, we could load the other impacts by a factor of three, reflecting how important a good community impact score is to the organization.

We then multiply each ‘raw’ score by its weighting.

Scroll the example below to compare the two.

As you can see, given the more complete operational context of our organization, the in-house project option is now preferred.

We will show you another weighted MCA example in the topics on procurement.

What happens if we don’t get the result that ‘feels’ right?

Multi-criteria analysis is an aid to decision-making – it should not make the decision for you.

When choosing to initiate a project, you should always draw on the experience of your stakeholders in exercising your best judgment on how to proceed.

Nevertheless, MCA is a powerful tool that not only reveals how you came to your recommendation; it compels you to follow a best-practice process in arriving at the optimal project decision.

Recommendation detail

At this point, you are only recommending that the preferred option proceed to detailed project planning.

This is because we still need a lot more certainty about the project and its deliverables.

At a minimum, we want to reduce our business case margin of error of ±20% to a more manageable (for the organization) ±10%.

By taking a deep, bottom-up dive into our project, we may also reveal new information that invalidates the assumptions of our business case.

For example, we may discover that:

- our cost estimates are wildly optimistic

- the delivery window is not practical

- certain scope elements will be impossible to produce

- legitimate stakeholder concerns were ignored, or

- other project or business demands conflict with our project.

In that case, we must return the project to initiation, inviting decision-makers to reconsider (or recommit) with the newly available information.

Regardless of how you present them, your recommendations need to be SMART.

What are you recommending?

Your recommendation needs to be specific, in that it targets a specific area for improvement.

What outputs / outcomes do we expect?

Your recommendation needs to quantify (or at least suggest) measurable indicators of progress and success.

Who will be actioning this?

Your recommendation needs to specify who is assigned responsibility for delivering the recommendation.

How will we deliver this recommendation?

The result you expect to achieve must be realistically resourced.

Note: some later sources describe A as achievable / attainable and R as relevant / realistic.

Given the interchangeability of these terms, we prefer the original author’s intent.

When can the recommendation be delivered?

Specify the time frame to achieve the result(s).

Source: Doran, G. T. (1981). “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives“. Management Review. 70(11): 35–36.

Did we just cover the triple constraints!? Yes.

A good recommendation might therefore look something like this:

- It is recommended that detailed planning commences on Option B.

- A complete project plan is to be presented for Board approval in four (4) weeks time

- The plan should continue the assumptions made in the business case, and include a detailed WBS, schedule, budget, stakeholder and risk registers, and any other documentation deemed relevant by the project management office (PMO)

- The PMO should also immediately appoint a suitably qualified project manager and project steering committee

- If the planning process invalidates the assumptions of the business case, the Board should be duly advised, and a new course of action recommended

- It is proposed that a budget of $15,000 be allocated to planning the project, inclusive of all staff labor and expenses

Other recommendation detail might include:

- Planning constraints: High-level time, cost, scope and quality expectations

- Critical success factors: Resource availability assumptions; other project dependencies; key stakeholder relationships; known project risks