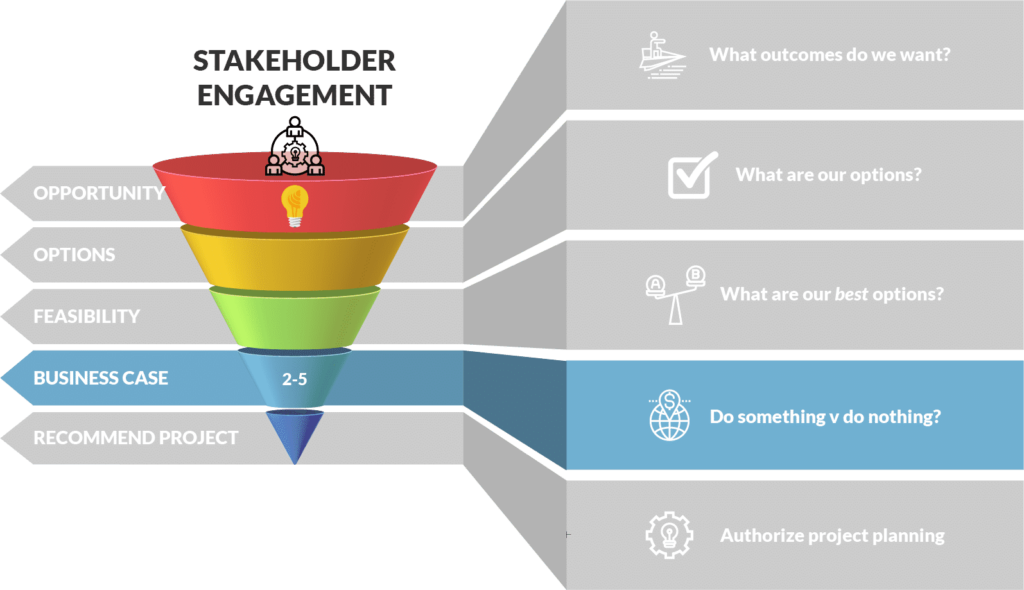

The business case

The business case documents the rationale for a project, justifying investments of time and money in pursuit of an opportunity.

Importantly, it challenges the sponsoring organization to weigh the merits of doing something (from one or more project options) versus doing nothing and continuing to invest organizational resources into other activities.

A ‘business case’ that does not evaluate at least one project solution against the null option (doing nothing) is only a project charter.

Even if, as the project manager, you do not prepare the business case – for in many organizations the business case is prepared by the project client or a dedicated business analyst – you should be a key contributing stakeholder in its development or able to critically interpret its findings once they land on your desk.

As you will see, the business case affords our one and only opportunity to benchmark the outcomes intended by the project, linking them to the strategic priorities of the sponsoring organization.

Without this context, projects can often flounder or fail to meet stakeholder expectations, especially in the face of change.

Like all project documents, the quality of the business case depends upon the quality of the data that informs it

This, in turn, depends on the assumptions and estimates made by its author.

The importance of accurate estimates

Estimation is one of the most important project management skills.

If you under-estimate the time and resources required to deliver a task or project, then (per the triple constraints) you may have to sacrifice either scope or quality to deliver the project.

This may be difficult to explain to stakeholders, especially if you have a fixed budget or delivery date.

Conversely, if you over-estimate the time or costs required, you penalize the organization by locking away valuable resources that could be spent on other projects or operations.

Even though it might be your best intention to return unspent requirements, Parkinson’s Law suggests that you will still find a way to spend them!

Alternately, at the initiation stage, your project may be rejected on the grounds that it will take too long or be too expensive.

If you are tendering competitively for project work (even within your organization), your over-estimate could cost you the job.

Deliberately over-estimating time or costs is a technique colloquially called padding, and we will discuss the strategic risks of this later in the course.

For now, though, at the business case level, we would like to be as accurate as possible in estimating the time and costs required to deliver each of our three, four, or five identified options.

So how accurate do we need to be?

It is widely held that a 20 percent margin of error is acceptable at this stage; however, your organization may have its own policy in this regard.

Plus or minus 20% means that we will tolerate our business case cost estimates being 20% ‘wrong’ either way, but any more than that is considered unreliable for decision-making.

Now 20% seems like a big margin of error; however, keep in mind that all we are doing at the business case level is comparing options so as to arrive at a preferred project solution.

When we take this option to project planning – the next stage in the project’s life – we will revisit and refine our cost estimates to within ±10%.

However, this is a much more detailed (that is, expensive to undertake) process and more effort than it is worth for business case decision-making, as we shall see.

Note, though, that the 20% margin of error is a refinement of the ±30-50% we were happy to accept at the opportunity definition / project concept canvas stage.

Basic estimation methods

So, how do you estimate time and cost?

Independent research

A good starting point for estimation might be reviewing past project plans or databases that might provide reliable information on past time and cost performance.

We can also consult various other current sources, including supplier catalogs, quotes, and good-old Google.

By applying analogous logic, even if we cannot get accurate data on precisely what we want, we can make ‘like-for-like’ assumptions.

For example: If it costs $17 for a tin of red paint, it will probably cost the same amount for a tin of blue paint (of the same quality).

Simple statistics

When working with a range of known data (or expert estimates), we frequently rely on these basic statistical methods to determine the most likely amount:

- Mean (the average score)

- Median (the ‘middle’ score)

- Mode (the most frequently occurring score)

For example: We polled our stakeholders, and they arrived at the following cost estimates for a tin of paint: $10, $10, $12, $15, and $18.

- The mean (average) = ($10 + $10 + $12 + $15 + $18) ÷ 5 = $65 ÷ 5 = $13

- The median (‘middle’) = $12

- The mode (most frequently occurring) = $10

Old-school project managers will also refer to three-point estimating, a weighted average technique from the PERT project methodology.

Parametric estimates

Parametric estimates take uniform (or even reliable analogous) information and apply a consistent multiplier.

For example: If it takes one hour to paint one room, then it should take five hours to paint five rooms of an equivalent size.

More sophisticated parametric models might also apply learning curves that calculate the time gains that can be achieved when specific activities are repeated many times.

For example: If it takes one hour to paint one room, then it should take four hours to paint five rooms of an equivalent size, because we will get better at painting over the course of the task.

Consensus method

Although we might consult or involve our expert stakeholders, combining their specialist knowledge to arrive at a range of estimates, the consensus method demands they agree on what the ‘true’ estimate (or range) might be.

In other words, instead of applying a statistical formula to their estimates, our experts are challenged to justify, defend, and affirm their estimates through collaboration.

Although this method is more subjective (and time-intensive), with the right people in the room, you can achieve very reliable estimates.

For example: Your painting experts might discover hidden or latent conditions in the room (such as moldy walls) that demand a different approach.

Independent cost assessment

On options where there is a high level of complexity, that are particularly specialized, or where the outputs are unique in that they can’t be templated, you may also like to consider getting an independent cost assessment.

An independent cost (or time) assessment can either review and validate your existing estimates, or directly source estimates using methodologies or expertise that is not ordinarily available to you.

The principal role of a quantity surveyor, for example, is to independently assess the materials, time, and labor costs of construction projects.

As with all estimation methods, independent assessments can be done at any time during the project’s life, but their optimum value is realized when they are conducted during the initiation or planning phases.

Other statistical methods

This is not a course in statistics; however, you should be aware that a range of other, advanced financial and statistical models can be used to estimate cost and time.

As always, you should look to engage your stakeholder community whenever you lack confidence in your own (or others) ability to provide sufficiently reliable estimates.

The margin of error we introduced in the last lesson is also known as the confidence interval.

Therefore, for each estimate, you should always document how ‘confident’ you are (for example ±12%), the sources you consulted, and the estimation method you used.