Chartering the project

The document that authorizes project planning is also known as the project charter.

The project charter establishes a partnership between the project manager and sponsor, and documents initial requirements.

Chartering a project also links stakeholder expectations of the project to the strategy and ongoing work of the organization.

As the final output of the project initiation process, the project charter documents:

- High-level requirements: the project’s scope

- Target milestones: the project’s schedule

- The project’s expected budget within a ±20% (or organisationally acceptable) confidence interval

- Project acceptance criteria: in other words, what constitutes project completion, who decides the project is complete, and who signs off on the project

- Critical success factors: these might include any key assumptions, dependencies, or risks that the project manager needs to know

- Authorization: the name and authority of the sponsor or other person(s) authorizing the project

The charter is then assigned to a project manager, at which point their responsibility or authority is clearly defined.

This is also when the project governance group is convened and given terms of reference.

Depending on the size of a project and the relative risk it presents to the organization, a project charter can be either a big, formal document, or something as simple as an email saying get on with it.

When the concept canvas authorizes project planning (in low-risk circumstances), it too is an example of a project charter.

The written business case is another example of a project charter that we look at below.

Although the charter is often compared to a contract, as it has a similar intention in many respects, it should not be confused with an actual contract.

Even if a contract to deliver a project output exists between a third party and the performing organization, a charter is still required to internally direct resources (including a project manager) to the project.

After all, a contract will not provide the level of detail necessary to actually deliver the work.

Although a limited allocation of resources may be made in the charter for planning to be completed, approval of the project plan is the real green light to start spending time and money delivering project outputs.

From business case to charter

It is not your money.

If the purpose of a business case is to persuade an organization to invest in your project, then the purpose of the project charter is to authorize you to start spending their money.

Therefore, a defining attribute of the project charter is that it is a written agreement.

Although the opportunity may be pitched and even sold in an elevator, boardroom, or to a TV studio audience, for the business case to be effective as a charter, it should document the following.

Introduction

To start with, you need to set the scene.

Give a little background and describe the context of the work unit or organization that you represent.

Next, you need to state the purpose of the report.

Implicit in this is the notion that the project proposed by this business case will solve a problem presently faced by the organization.

You should also explain how the report will work.

Describe briefly and logically the steps you will go through to address the issue.

Opportunity definition

Updating the early thoughts of the project concept canvas, this next section is intended to change how the business thinks about the situation.

To do this, when you identify the problem, you should contrast the current state of the business with an ideal future state.

In other words, what organizational outcomes do we intend to deliver?

You can also list the things that are out of scope; this is, outcomes your solution will not address (for budgetary or other reasons).

You should finally explain why the problem matters, linking it to the objectives of the performing organization.

Methodology

To establish the authority for your business case, you should detail the primary and secondary sources consulted.

Primary sources are stakeholders you consulted directly for information to develop the business case.

Secondary sources come from your ‘desktop’ research – authoritative reports, cases, reviews of like projects et cetera that you drew on.

By attaching the credibility of these sources to your report, you are, in effect, challenging your audience not to argue with your findings; in other words, you are stating that the recommendations of this report are more than just one person’s opinion.

It is, therefore, important that you do not undermine your report by misquoting or otherwise misrepresenting these sources – you will be found out!

It is also useful to list in this section any assumptions that might be present in your analysis, and the limitations or constraints placed on your study.

Included here might be assumptions about (or constraints relating to) scope, schedule, cost, quality, risk, stakeholders (including stakeholders not consulted), and procurements.

Consider, too, the implications if an assumption is wrong.

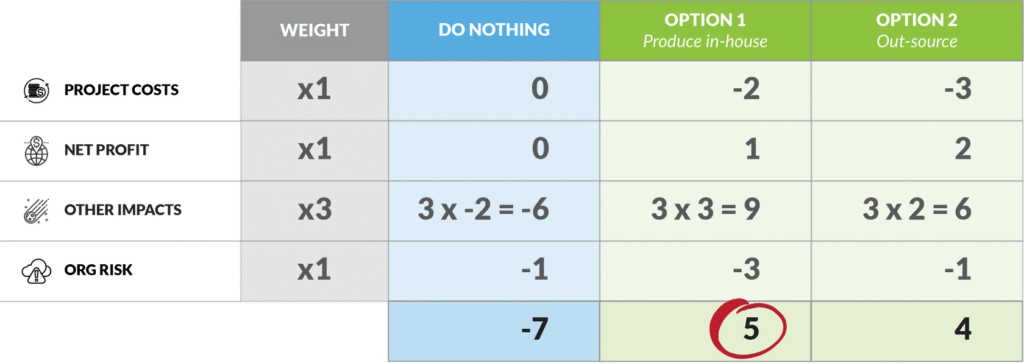

Options analysis

Analysis of options is the whole purpose of the business case (a point you should probably make in the introduction).

To convince someone to pay for your project, you need to show more than just one solution to the problem – you need to prove the best solution.

Option Zero is always the null hypothesis: this is what will happen if we let things continue as they are.

The next options – and you should list no more than two to five – should be presented in sufficient detail for decision-makers to tell the difference between them and their outcomes.

In doing so you must describe the costs and impacts of each option, and assess the risks to the organization of proceeding with them.

Some introductory narrative around feasibility may also be appropriate for each option, even though this may not be an explicit criterion for final ranking.

Conclusion

Your conclusion should be a clear statement of preference for one of the options.

This preference should be ‘obvious’ from the analysis of alternatives presented.

In other words, this is the place for your multi-criteria analysis.

You might also like to highlight some of the factors that are critical for the realization of this project, and some of the criteria that will enable stakeholders to judge project success.

Recommendations

Your recommendations are a call to action for your decision-makers.

You should organize your recommendations by priority or time sequence.

For each recommendation, you should have a bold, headline sentence (like the headline on a newspaper article).

And make sure you stay SMART!

Appendices

Appendices are attachments to your main report.

Any appendices that you include must be relevant and not just for padding.

An appendix will provide details on any contestable evidence or statements of ‘fact’ that are introduced in the body of the report.

A complete feasibility study is an example of a document that might become an appendix to a business case; other appendices might include:

- A glossary of acronyms

- Definitions / business rules applied

- Detailed cost breakdowns

- Financial spreadsheets

- SWOT / PESTLE analyses

- Detailed data tables

- Technical specifications

- Legal / regulatory requirements

- Supplier quotes / expressions of interest

- Relevant correspondence

- Useful contacts

- Configuration history

Executive summary

The executive summary sits at the front of the report.

It is the single most important element of the business case, if for no other reason than 90 percent of users will never read anything else.

An executive summary is not an introduction or a movie trailer, teasing audiences about what will come.

It contains a summary of all the vital information from the report, including your top three recommendations.

As a rule, the executive summary should be no longer than two or three pages, or 10% of the word count of the business case.

Critically, you absolutely cannot write the executive summary until the rest of the report is complete.

You should be aware that in many instances, the requesting organization or client may independently initiate the project

As the project manager, you might only inherit and have no prior say on the project effectively chartered for you.

This is especially frustrating when you are handed poorly developed treatments or ones with unrealistic expectations.

If that is the case, you should raise your concerns with the project sponsor as soon as it is practical to do so, and by no later than the end of the project planning process.

Be prepared though to fully evidence your arguments, even if this means deconstructing the existing project logic line-by-line.

After all, by this point the key stakeholders, including the sponsor, have probably invested a lot of effort and ego into the project.

Download free-to-use simple and detailed templates for the project business case here.

Project sizing

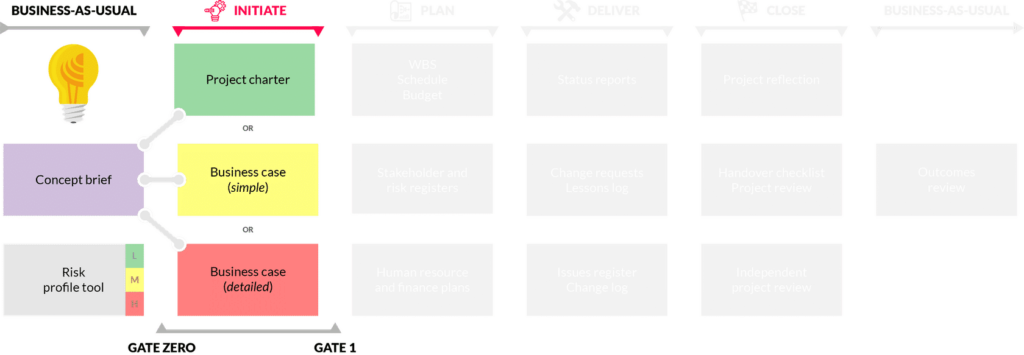

In some circumstances, you can skip the business case and go straight to chartering the project.

On small or low-risk projects, following the full initiation process is a redundant use of resources and the concept canvas may be sufficient to initiate the project.

Other projects simply must be done – for example, if a client orders a specific output from you under contract, the business case for it can be assumed (or at least validated as part of the contracting process).

And in some cases, the risk of not proceeding is obviously greater than the impact of doing nothing, such as when a change in legislation necessitates updating a process.

As we saw earlier, you should always run each opportunity canvassed through your risk profile tool. If accepted:

- Low-risk opportunities can be chartered on the spot

- Medium-risk opportunities should be allocated the resources to prepare a simple business case, and

- High-risk opportunities should demand a detailed business case

This point in time is known as decision gate zero.

A decision gate allows the sponsoring organization to formally decide whether to proceed with, send back a step, or terminate a project.

The next go/no-go point in a project’s life is at the end of the initiation process – gate one – when project planning is authorized or refused.

We will introduce other decision gates as we proceed through the project lifecycle and this course.

A final word…

A project manager may go their entire career and never prepare a business case or even be involved in project initiation.

Unfortunately, many organizations feel they successfully deliver projects without formally going through these steps, going straight to project planning or even delivery.

We often hear executives say, look – there really is only one option, we don’t need to do anything else… let’s just get on with the project.

And they’re probably right – about five percent of the time.

For even if you have only one standout option, you can almost guarantee there are options within it that are worthy of more detailed consideration.

For example, what if we fast-track delivery by 20%? What do we lose? What do we gain? What if we add a few more features?

Or, more critically, have we under-represented or even missed the input of a certain key stakeholder? Have we assumed they will think one way, without asking?

So what are the benefits of properly initiating a project?

Context

The process of project initiation gives the project context.

Done well, it significantly reduces ambiguity for both the project manager and stakeholders, which – as we know – reduces the need for and cost of change in project delivery.

To the project manager’s benefit, the process further details and documents:

- What options have been considered – what is in and (by implication) out of scope?

- What assumptions were made (for example, about time and cost)?

- How important or risky is this project to the organization?

As you will also see, making the organization’s decision-logic transparent makes change management much easier once project planning and delivery commence.

Assets

The concept canvas and business case are the assets that provide context to the project team.

Another important legacy of the initiation process is the stakeholder register.

The project manager who inherits this asset enjoys a significant head start in one of their key functional roles: liaising with stakeholders and managing their expectations.

The stakeholder register also insures the project against imperfect stakeholder memories of whether or not they were given adequate opportunity or scope to engage with the original idea.

Lessons learned

When things go right or wrong, the outputs of the initiation process – the concept canvas, stakeholder register, and business case / project charter – are critically important inputs into project closure and review.

They provide another window not just into the project itself, but the justification for and decision-making process that led to the project being initiated in the first place.

After all, a perfectly executed project is pointless if it was never the right project in the first place.

Following the initiation process should always be the default; you should have a very good justification for skipping this step.

It is far better to explore all options and make relevant discoveries now than when it is too expensive or just too late further down the track.