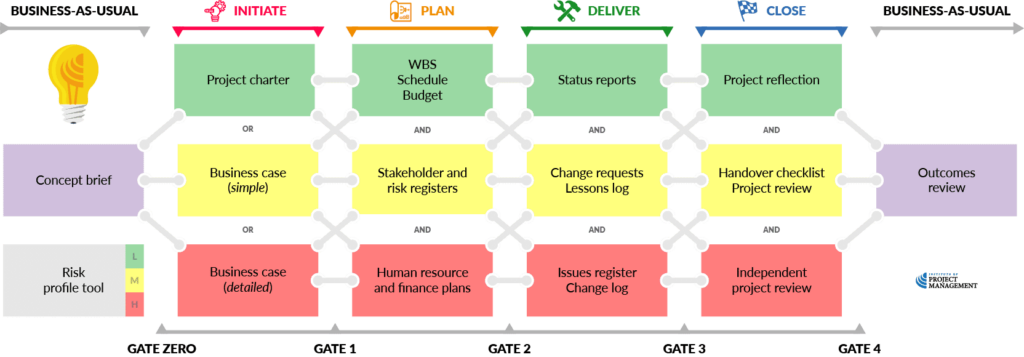

Tools and templates

Project documents – which are known elsewhere as organizational process assets – are at the center of any methodology.

Although they are increasingly being raised in dedicated project software, many organizations still use word-processing or spreadsheet applications to maintain them.

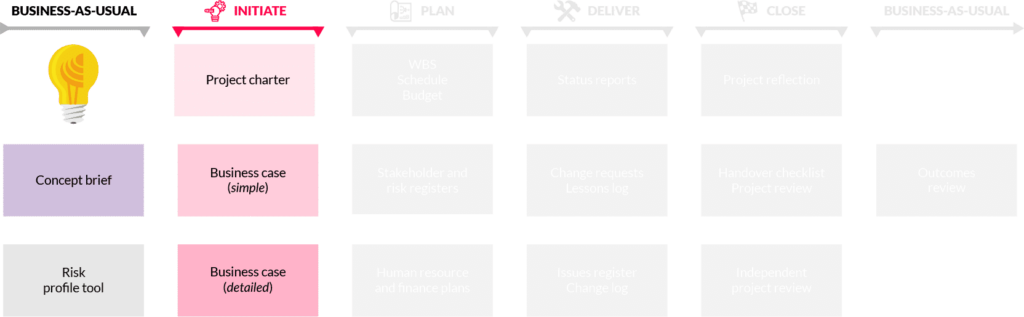

The following infographic shows the point in the project lifecycle when they are typically developed or delivered; however, this is a loose categorization.

Each may be developed earlier and/or used later, depending on the project’s needs.

Initiate

Concept brief

A concept brief first documents the idea that may become a project someday.

It defines the opportunity, links it to the organization’s objectives, and names up the outcomes that could be realized if all goes to plan.

It also gives early consideration to potential time and cost constraints and who some of the key stakeholders might be.

Risk profile tool

The risk profile tool assesses the relative risk to the organization of proceeding with an opportunity or project.

It not only enables a diverse range of opportunities/projects to be evaluated on a like-for-like basis; properly applied, it can recommend an appropriate level of project management and governance.

Project charter

The project charter is the document that formally authorizes project planning.

It establishes the partnership between the project manager and sponsor, and documents initial requirements.

Chartering a project also links the stakeholder expectations of the project to the strategy and ongoing work of the organization.

That said, we will show you in Unit 3 how a good concept brief or business case can double as an effective project charter.

Business case

The business case captures the reasoning for initiating a project or task.

It considers alternative ways that a conceptualized opportunity might be realized and – using consistent criteria – recommends the optimal project solution.

The logic of the business case is that whenever resources are directed toward a project, they should be in support of a specific business need.

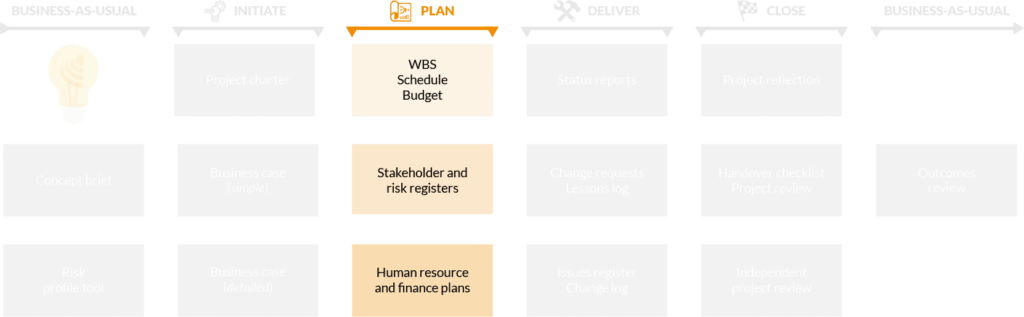

Plan

WBS, schedule, and budget

The work breakdown structure (WBS), schedule, and budget are the cornerstones of the project plan.

As per the triple constraints, the WBS documents the scope, the schedule documents the time, and the budget documents the project’s cost.

The three are often presented in a single, integrated plan and are the baseline from which project delivery performance is measured.

Stakeholder register

A good stakeholder register doubles as the project’s communications plan; therefore, it is one of the first documents created, and one of the last ones retired.

It contains stakeholder identification and contact information, prioritized classification of their power, interest, level of engagement, and expectations and interests.

It should also document stakeholders’ communication preferences and include a log of all your contacts with them.

Risk register

At its most basic, a risk register is a high-level, summary view of all project risks and their status.

Sitting behind that may also be a detailed assortment of factors relevant to each risk, such as risk owners, prioritized analyses, agreed actions and contingencies, and how each risk will be monitored and controlled.

It is important to note early that this document may differ from the standard register of organizational risks, something we will explore in more detail in Unit 7.

Human resource and finance plans

Complex projects with large internal teams and/or significant transaction volume may also require the development of specific human resource and finance plans.

These are but two of a range of planning documents that can support project delivery, although they should not be mandatory for every project you undertake.

At the end of the module on project planning, we will discuss how to scale these additional plans to fit the needs of your project best.

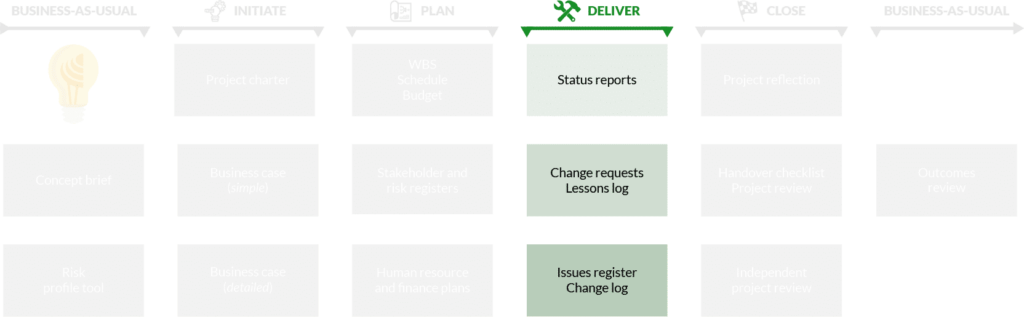

Deliver

Status reports

As the name suggests, status reports update stakeholders on the ‘state’ of the project.

In their documented form, they will (at a minimum) cover work completed since the last status report, work to be completed in the next period, and any issues or risks that need to be brought to the reader’s attention.

Formal status reports may also use statistical methods to show project progress against the planned baseline expectations.

Lessons learned register

If one hasn’t been started earlier, it is useful to document hard-won project delivery experiences in real-time using a lessons-learned register.

Especially in projects of long duration and significant complexity, this tool makes the project reflection and review process much easier by ensuring that even micro lessons are not lost to your organization.

Change requests

It is important that all relevant stakeholders are engaged through a formal project change management process whenever it is necessary to vary the project plan – and it is quite often necessary.

The change request template supports this by documenting a mini-business case for each change, capturing the authorization of the organization, and subsequently tasking the project team.

Issue and change logs

It may also be useful to document the status of these changes in a register or log on complex projects.

This log acts as an index that points to the individual change requests and facilitates an “at a glance” summary of where each change is up to.

As a complement to the risk register, a log of issues the project is experiencing may also be of similar benefit.

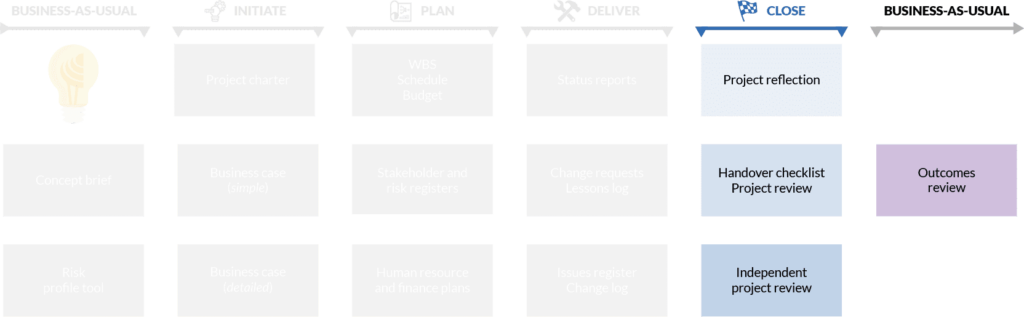

Close

Project reflection

Although every project team member will inevitably reflect on their performance, a project reflection template will structure the process.

This document is similar in intent to the lessons learned register (and may depend upon it) in that it captures and retains the knowledge gained through the four stages of the project’s life.

Project reflections can also be useful from an organizational perspective, as the meta-data they provide might inform the continual improvement of project delivery across the entire enterprise.

Handover checklist

Ideally prepared in the planning phase (and updated as any relevant changes are realized), the handover checklist is an important document that facilitates the final transfer of the project’s outputs to the client.

Not only does it give the client certainty that what they requested is what they are receiving, but it can also be a useful internal tool for verifying that the project is, in fact, complete and that there are no outstanding requirements.

Project review

A project review is a more detailed examination of the circumstances and performance of a project.

It typically involves poring over the project documentation, interviewing key stakeholders, and conducting a detailed, almost forensic-level analysis of what went right and wrong.

Although it may be conducted internally within an organization, a level of independence from the key project stakeholders is nonetheless required to reduce the possibility of bias coloring its findings and recommendations.

Outcomes review

The outcomes review assesses whether or not the project’s outputs actually went on to achieve the outcomes initially intended by the concept brief and business case.

As these outcomes are more often than not realized a long time after project handover, the outcomes review usually sits outside the project lifecycle.

As such, its conduct is the responsibility of the output owner (the client), and the project manager is merely one stakeholder who may be consulted.

In the next lesson, we will examine why these documents matter and how they should be applied in organizations.

Why they matter

Templates can be a great aid to projects.

They help guide more junior team members through the planning and reporting processes, ensuring that they capture vital information.

They are one way that organisations can educate staff on the importance and need for capturing certain information.

Templates can be valuable for more experienced project managers, too.

They provide structure and act as a checklist for data that needs to be captured, so it is less likely that something will get accidentally overlooked.

They also speed decision-making by presenting information in a consistent, relatable format.

That said, sometimes, all a good project plan does is document your failures with greater precision.

Although this scenario is the exception, it is possible to have a perfectly documented project that somehow finds a way to fail.

Importantly, project documents should support and enable project delivery instead of getting in the way.

Sometimes the constraints of documentation can frustrate the work of the project. This will manifest as general inefficiency, missed opportunities, and poor staff morale – don’t be overly bureaucratic!

It is also well documented that using the same format or template over and over can cause users of the output to miss important items that may need to be included.

In the same way, ‘save-as’ syndrome – where new plans for a project are copy-and-pasted version of a similar project – can not only cause errors to be repeated but stagnate independent and creative thinking.

It is important to note that while following a documented process may be a minor nuisance to the project team, the positive outcomes enjoyed by all stakeholders usually make the process worthwhile.

That said, not every process needs to be used on every project.

If using a template adds time to a task because you are doing so much modifying and deleting while trying to shoehorn your project into the defined format, then you need to either seek advice or let it go and start from scratch.

Keep the end in sight – challenge the value that each process delivers relative to the objectives of the project and your organisation.

We will address this balance more directly as we move through the program; for now, though, recognize and appreciate that a project structured around some key, enterprise-specific documents can bring the previously stated benefits of methodology to the organization and the team.