The iron triangle

In project management, we often refer to the ‘triple constraints’ of time, cost, and scope.

Others more dramatically refer to them as the ‘iron triangle.’

At the center of this triangle is quality. It’s at the center because changes to time, cost, and scope all impact (or constrain) quality.

As project managers, we often use this triangle to illustrate why agreement on these factors is necessary and how seemingly minor changes to scope, time, or cost can have significant repercussions.

Let’s see how…

Time

Because projects are defined by their start and finish, they have a finite and necessarily limited time for completion.

Ideally, we would like to complete our projects as quickly as possible.

It is no secret, however, that the more we rush tasks, the more likely we will fail to set out what we intend to achieve.

Therefore, if we reduce the time available to a project, we potentially reduce its quality.

Conversely, the more time we make available, the more likely it is we can anticipate, identify and address the various issues that arise during the performance of our project.

For example: If we leave our holiday shopping until the last minute (reducing time without changing cost or scope), the quality of our purchases may suffer.

Cost

Similarly, the more money we have at our disposal, the more likely it is that we can meet our objectives.

Keep in mind when we say cost, we really mean resources, such as labor, materials, equipment, and infrastructure.

Cost is just a shorthand way of referring to all of these things, as all these resources are ultimately recorded in dollars spent.

So, assuming that the project’s scope and available time are held constant (that is, they remain unchanged), increasing a project’s budget will theoretically give us more resources to complete the job, improving the quality of outcomes.

By the same token, if we are required to do the same work in the same time but with less money, we may jeopardize the quality of our project and its deliverables.

For example: If we increase our budget for holiday shopping (increase cost without changing time or scope), the quality of purchases will also increase.

Scope

Scope, though, is a different story.

When we talk about a project’s scope, we are referring to all the things that need to be done to successfully deliver our project.

This will include all our technical or functional requirements, such as putting up the four walls and roof of a house, as well as the project management requirements, such as planning, managing delivery, and closing the project.

If we increase the scope of a project – for example, we need our house to be bigger – but expect delivery by the same deadline and for the same cost, we make the project more complex, and complexity is potentially the enemy of quality.

After all, the simpler a project is, the easier it is to manage and deliver.

Likewise, if we enlarge the project management processes – for example, by imposing a large number of reporting requirements – we have once more added complexity to our project.

Now this might be necessary to ensure quality, but without factoring in a proportionate increase to our schedule and budget, we have actually made the project harder to deliver by theoretically squeezing out other tasks.

Therefore, an inverse relationship is observable: as long as time and cost are held constant, increasing scope will likely decrease quality.

For example: If we suddenly realize we need to purchase more gifts (increasing scope without changing time or cost), we are likely to reduce the quality of what we are able to achieve.

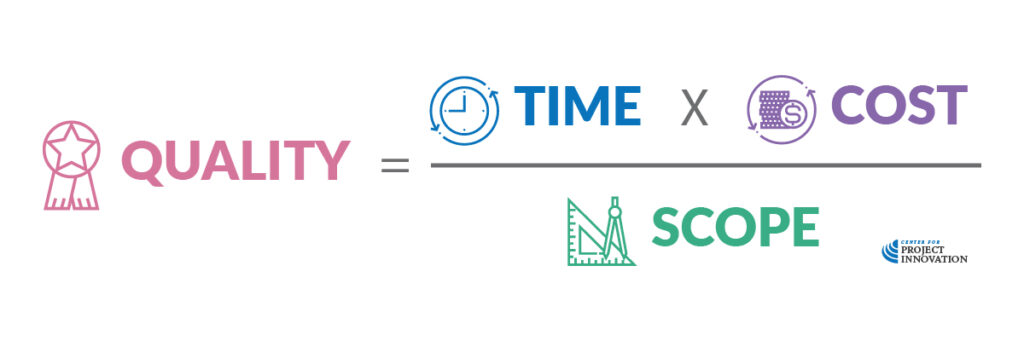

Formula

The mathematically minded among you may appreciate the triple constraint relationship being expressed in the equation illustrated above.

For example: If, in a perfect world, our project has 5 days and $500 to deliver 5 tasks, applying the triple constraints formula ((5 x $500)/5)) will give us a quality score* of 500.

Changes to time

- If we only have 2 days and $500 to deliver the 5 tasks (reducing time), applying the formula ((2 x $500)/5)) will give us a lower quality score of 200.

- If we allow 10 days and $500 to deliver the 5 tasks (increasing time), applying the formula ((10 x $500)/5)) will give us a higher quality score of 1,000.

Changes to cost

- If we have 5 days and only $200 to deliver the 5 tasks (reducing cost), applying the formula ((5 x $200)/5)) will give us a lower quality score of 200.

- If we have 5 days and $1,000 to deliver the 5 tasks (increasing cost), applying the formula ((5 x $1,000)/5)) will give us a higher quality score of 1,000.

Changes to scope

- If we have 5 days and $500 to deliver 2 tasks (reducing scope), applying the formula ((5 x $500)/2)) will give us a higher quality score of 1,250.

- If we have 5 days and $500 to deliver 10 tasks (increasing scope), applying the formula ((5 x $500)/10)) will give us a lower quality score of 250.

*Note that a ‘quality score’, as it is expressed here, is only hypothetical – it is used to numerically illustrate the concept that quality can be high or low. In real life, we measure quality in a number of different ways that we will discuss further in the course.

Too much time and money?

Work expands so as to fill the available time for completion.

Cyril Northcote Parkinson (1909-1993)

Note that we have been using words like “potentially” and “likely” throughout this discussion.

Parkinson’s Law suggests just giving more time to a project might only result in people dropping their productivity to fill the slack.

Similarly, if you give one project $5000 to complete the work and an identically scoped project $10,000, chances are they will both find a way to spend all of their budget!

Changes to scope, time, and cost will only change the quality of the deliverables by default if there is no management intervention; this is where the project manager’s skill comes in.

For example, a poorly defined scope – and by that, we mean we only have a vague idea of what it is we are setting out to do – is far less likely to deliver a quality outcome than a slightly more complex project that is really well defined, understood and agreed to.

Similarly, an experienced and effective project manager can usually do more with less. In other words, given the same constraints as a less experienced and effective colleague, he or she should be able to deliver a higher-quality product, service, or result.

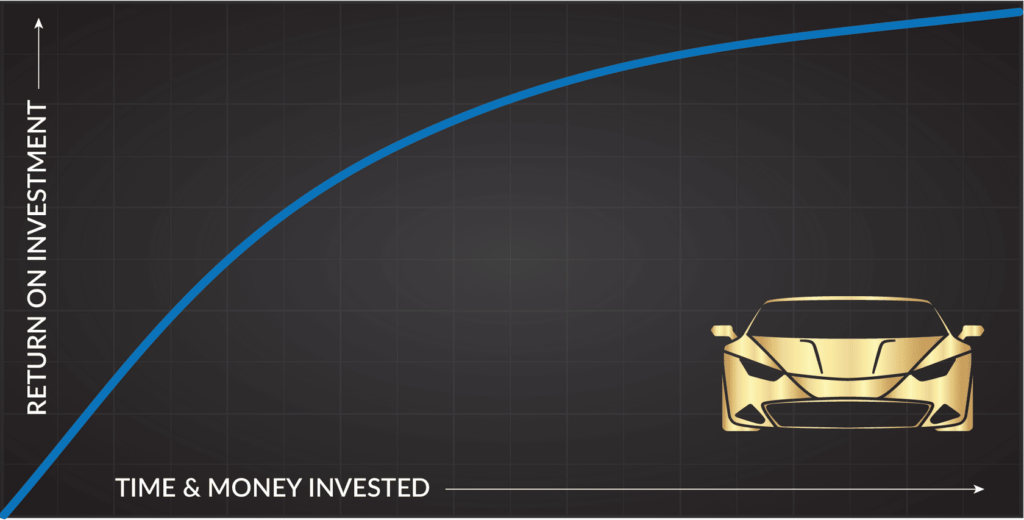

You should also be aware of the law of diminishing returns.

Early investment

Your investment of time and money in a project (output) is made in the expectation of a return (outcome).

It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the more time or money you invest, the greater the benefits returned.

Later investment

Perhaps counter-intuitively, over time, you inevitably get less return for each dollar or hour invested.

For example: An unhealthy person who commences exercising an hour per day will get huge, immediate benefits from their activity.

However, presuming those benefits are locked in after the first year, the same exercise will yield less rapid improvements in fitness or body mass over each succeeding year.

Marginal returns

In project management, the value of every additional hour or dollar must be weighed against the benefit it will deliver to the project’s output or outcomes.

At some point, it becomes unjustifiable to make additional investments of time or money as they yield no real benefit; they may even diminish the overall profitability or value of the project!

Gold-plating

This is a phenomenon known as gold-plating.

Essentially, it means adding (at a cost) features or extras without returning a corresponding return on that investment.

For example: literally gold-plating a car makes it less useful as motor vehicle (although if a desired outcome is the conspicuous and ostentatious display of wealth, then mission accomplished)!

Understanding quality

Finally, you should understand quality as both a process and an outcome.

Quality as an outcome refers to whether or not our deliverable or output meets the client’s requirements.

In other words, does it do what we said it would?

Quality as a process not only includes how we manage time, cost, and scope but other related activities such as risk and stakeholder management.

This quality management process that some refer to as integration – that is, the way we bring all the process elements together – is essentially what project management and this course are all about.