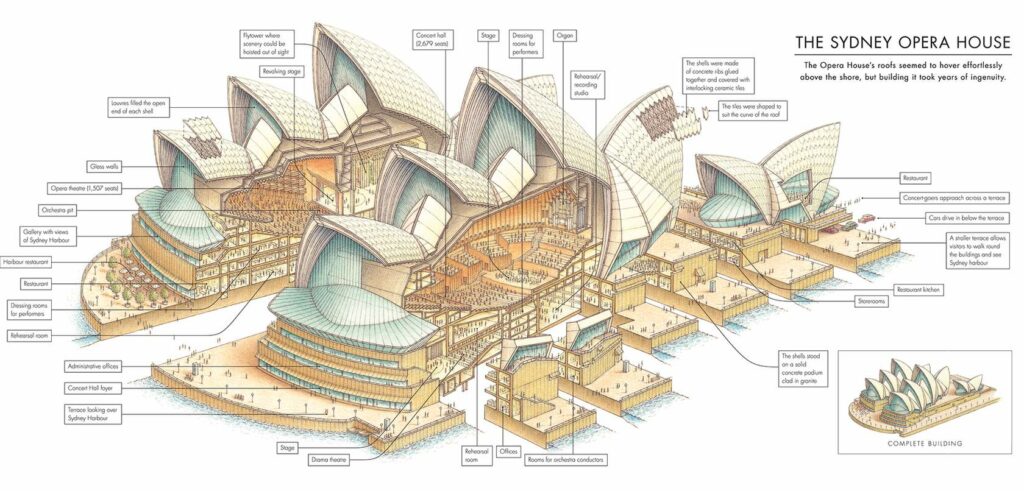

The Sydney Opera House

The Sydney Opera House is one of the twentieth century’s most distinctive buildings and one of the most famous performing arts centers in the world.

It was conceived in 1957 and largely built to Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s competition-winning design.

Utzon had designed the building without seeing the site in person, relying on photographs, shipping maps, and firsthand accounts.

In fact, Utzon’s submission did not meet the competition rules.

The judges put in place a process to evaluate entries but were disappointed that Utzon’s beautiful ‘sail’ design didn’t make it through and chose it anyway.

From 1957 to 1963, the design team went through at least twelve iterations of the roof-shells trying to find an economically workable solution.

Other significant changes to the design were also made, primarily because of inadequacies in the original competition brief, which did not make it clear how the Opera House was to be used.

The number of theatres was increased from two to four mid-project; the layout of the interiors was completely overhauled; and the stage machinery, already designed and fitted inside the major hall, was pulled out and largely thrown away.

- The original completion date set by the government was 26 January 1963.

- The original cost estimate in 1957 was £3,500,000 ($7 million).

The project was formally completed in 1973 (10 years late), having cost $102 million (15 times over budget).

So… was the Sydney Opera House project a success?

Definitions of success

The ‘perfect’ project is always delivered:

- On time

- On budget

- To scope

These criteria should be familiar to you as the triple constraints.

Yet as the Sydney Opera House example shows, these criteria are often elusive and may not even be definitive of project success.

Sure, the Opera House failed on cost and duration estimates, but it is one of a handful of real architectural masterpieces from the last century, and that metric was not on the project plan.

The Sydney Opera House also opened the way for the immensely complex geometries of some modern architecture.

It was one of the first examples of the use of computer-aided design to design complex shapes. It was also one of the first in the world to use araldite to glue the precast structural elements together and proved the concept for future use.

In 2007, the Sydney Opera House was made a UNESCO world heritage site.

Success comes in different shades and is ultimately a subjective standard.

As stated earlier, a project is just a means to an end. Project outputs will ultimately be judged on the outcomes they deliver; however, the project manager, sponsor, client, and user may each have different perceptions of success at each stage of the project’s life.

However, please don’t take away the idea that genius permits poor project management.

Admittedly the equally iconic Bilbao Guggenheim had access to more modern technology, but it was completed basically on time, on budget and to scope.

So what are the typical causes of project under-performance and/or failure, and (more importantly) how can project management help?

Avoiding failure

We now know:

- 48% of projects finish later than originally planned

- 43% of projects finish over their original budget

- 52% of projects experience uncontrolled changes to scope

In fact, 15% of all projects fail

In other words, for every $1,000,000 spent on projects, $150,000 is wasted.

Yet the causes of project failure are not secret, and they are not random; the purpose of a project methodology is to reduce and eliminate these known risks.

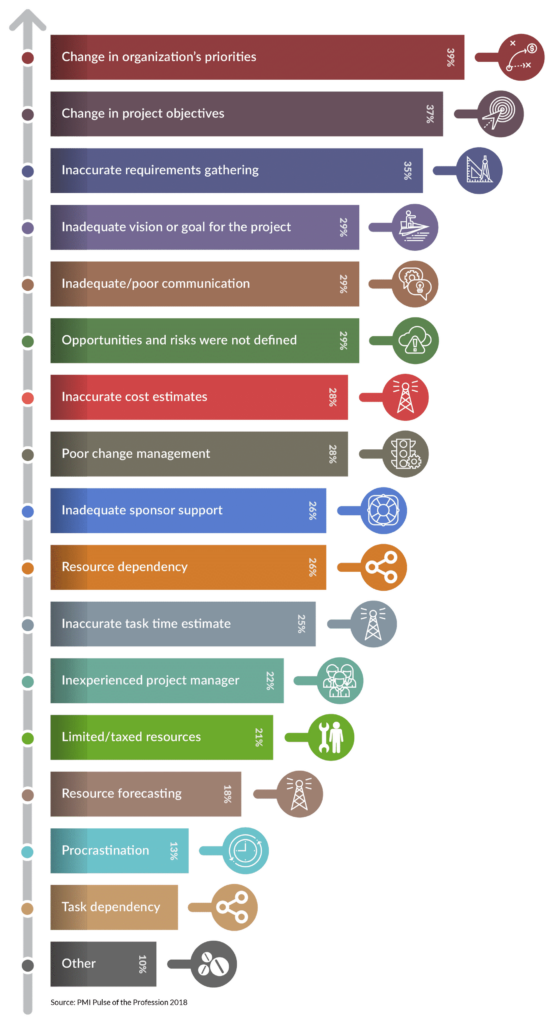

The chart below lists the causes of project failure as reported by a global, cross-industry sample of 4,455 project professionals.

As we proceed through this course, we will show you how to address each in turn and together.