3.5 Feasibility analysis

Critical thinking

Critical thinking involves reviewing all the options, ideas, or outcomes of our creative processes and objectively arriving at an optimal decision.

In part, it also involves making judgments about the quality of the information being considered.

In other words, do we have enough information?

Is it sufficiently reliable for our purposes?

And, if challenged, how can we prove this?

According to The Foundation for Critical Thinking, a critical thinker:

- Raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards

- Thinks with an open mind, recognizing and assessing their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences, and

- Communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

These are challenges that we will return to throughout this course.

For now, though, let’s assume that we have gathered a high-quality set of options and, in the following few topics, begin to critically deconstruct them to arrive at the best one.

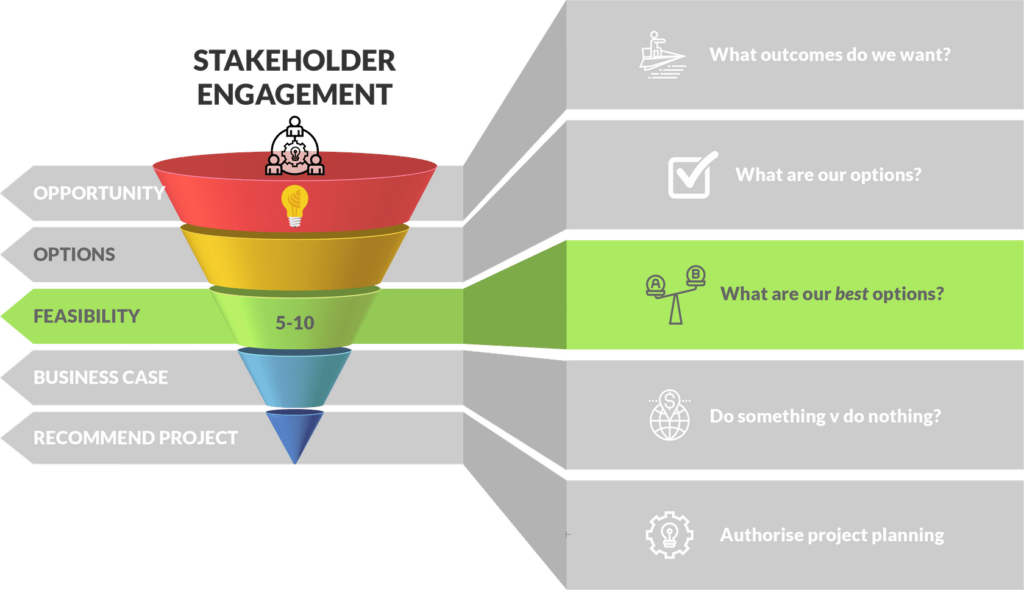

Feasibility analysis

Feasibility analysis aims to determine which options would make the best projects.

The two questions that need to be answered by any feasibility analysis are:

- Is this something people want (demand)?

- Is this something we can do (supply)?

Our purpose here is to reduce our myriad options identified to a small, manageable handful.

These can then be subject to more comprehensive, critical analysis in the business case.

Is this something people want?

Market analysis answers the question, “Is this something people want?”

It is assumed that the governing question – “Are these outcomes something the organization wants?” – has been answered in the affirmative by giving the green light to proceed past the opportunity definition (concept canvas) stage.

Now we need to test the demand for each of the options identified.

If you cannot substantiate adequate demand for your proposed product or service through research, then your project option is not feasible.

Some of the questions that might be part of your analysis include:

- Who is going to want this deliverable?

- What do these potential users have in common?

- How many of them are there?

- What equivalent products/services are already meeting this demand?

- How are these factors likely to change in the future?

Importantly, we must be able to evidence demand in some way.

This allows decision-makers to apply the appropriate degree of confidence to our estimates.

We will consider estimating error in much more detail as we go through this course.

Is this something we can do?

Technical feasibility asks, “Is this something we can do?”

In other words, do we have the organization capability and capacity to supply this option?

The cost and availability of skills, technology, and resources are critical to the feasibility of our project options.

Where there is a level of uncertainty about the legal implications of an option, you should also stop to ask, “Is this something we are allowed to do?”

Consulting with relevant regulatory agencies or legal experts may be necessary before proceeding.

You might also have internal policy constraints. For example, your employer or sponsor may have an intellectual property policy that prevents you from sharing certain trade secrets with third parties.

If such knowledge-sharing is necessary for the success of your project, it may not be feasible.

It may finally be helpful to conduct a basic financial feasibility assessment of the project; in other words, “Is this something we can afford to do?’”

In other words, do we have the working capital needed to deliver this project? If not, how likely is it that we can afford it?

Importantly, at this stage, we are only assessing high-level financial feasibility with very rough estimates – we will spend a lot more time and effort examining this with our remaining business case options and again in project planning.

Threshold v relative feasibility

Feasibility analysis is often conducted as a two step process.

First, we need to establish threshold feasibility.

This might involve asking some simple yes/no questions of each option along the lines described in the last lesson:

- Is this something people want? Yes

- Is this something we can do? Yes

- Is this something we are allowed to do? Yes

- Is this something we can afford to do? No

Taking this approach, we should be able to very quickly discard those options that are not worthy of further consideration.

To some extent, we almost certainly did this intuitively as we were developing our list of options; nonetheless, it is always a useful exercise to conduct before proceeding to the next step.

The remaining options are then analysed for their relative feasibility.

This may involve asking similar questions of each option, only this time we are comparing options relative to each other:

- Do people want Option A more than Option B?

- Is it easier for us to produce Option A than B?

- Is Option A more affordable than Option B?

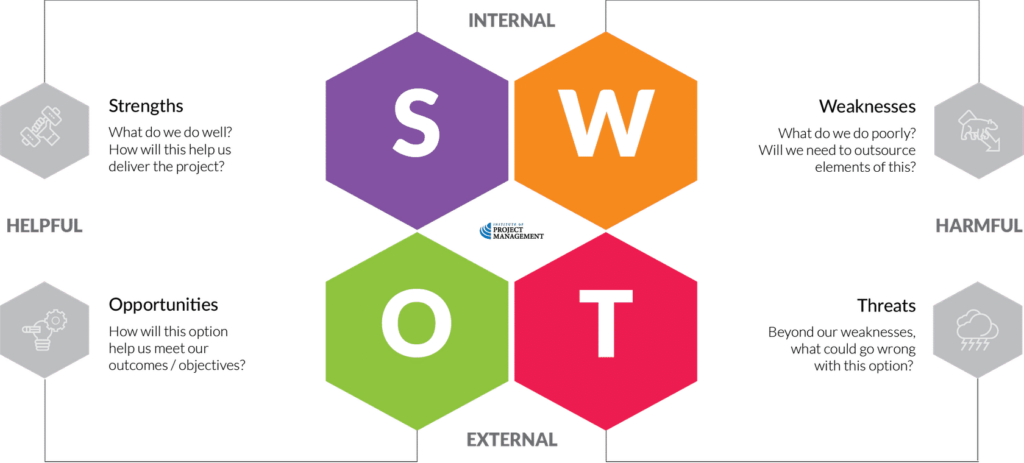

A helpful tool for this purpose is the widely employed SWOT analysis technique.

For each option that satisfies our criteria for threshold feasibility, we can ask what are its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

In other words, from our organizational perspective, what are the pros (strengths) or cons (weaknesses) of delivering each alternative as a project?

Similarly, from the market’s point of view, what are the opportunities each project might exploit versus the risks it might expose us to?

Other related techniques for analyzing the relative feasibility of options include:

Applied with an appropriate level of rigor (that, yes, involves thorough stakeholder engagement), we should be able to identify a short list of anywhere between two and four alternatives that are the ‘most’ feasible.

Taken together with the ‘do-nothing’ option, we can then proceed to the more detailed – and therefore time and resource-intensive – analysis of costs, impacts, and risks that is the business case.